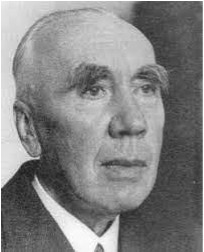

Rudolf Frieling – March 3, 1901 Leipzig – January 1, 1986 Stuttgart

Dr. Rudolf Frieling has been one of the most important representatives of the Christian Community since its founding. As a priest, he co-founded the congregations in Leipzig, Vienna, and New York. He made his influence felt through countless lectures and important writings, as well as through the publication of the magazine for the Movement for Religious Renewal. He was a leading teacher at the priest seminary for 50 years. He was part of the Movement’s leadership starting in 1929, before ultimately taking over as Erzoberlenker in 1960 and serving in that central position for 25 years.

Dr. Rudolf Frieling has been one of the most important representatives of the Christian Community since its founding. As a priest, he co-founded the congregations in Leipzig, Vienna, and New York. He made his influence felt through countless lectures and important writings, as well as through the publication of the magazine for the Movement for Religious Renewal. He was a leading teacher at the priest seminary for 50 years. He was part of the Movement’s leadership starting in 1929, before ultimately taking over as Erzoberlenker in 1960 and serving in that central position for 25 years.

Rudolf Frieling was born on March 23, 1901, in Leipzig. His father was a Protestant minister. Starting in 1902, he grew up with his brothers near the Rüdigsdorf Castle estate in Kohren- Sahlis, south of Leipzig, where his father served as a chaplain. There he could experience the wonderful natural surroundings of castle and park, which are linked with such names as Münchhausen, Schwind, Julius Mosen, and Rilke. His childhood was rich with sense-stimulating impressions, a “fantasy world,” as he called it. When he was three, one of his sisters died. The mantric form of the burial liturgy, which his uncle later had to repeat to him, gave him a deep experience of language.

When his father was transferred after seven years and became the resident minister in Chemnitz, the boy experienced this deliberate move from the country to the city as a “death sentence.” City and schools were a constant agony for his extremely sensitive soul. Nevertheless, he completed high school in the spring of 1920 with an outstanding Abitur (final exam).

Three experiences from his school days were especially important to Frieling: During a summer vacation in Warnemünde on the Baltic Sea, he was present when the German fleet departed. The result was a deep and life-long connection with the ocean, ships, and the navy.

Frieling also developed a special relationship with death stemming from the death of a teacher when he was 12, which shocked him deeply, and from a family life shaped by the many funeral services his father was obliged to perform.

The experiences during a vacation in Thüringen near the ruins of a cloister were so strong that Rudolf Frieling wanted to become a monk—and he immediately began to live like a monk and playact small rituals.

It had already become clear to him in high school during the war years that he wanted to study theology, and he started to do so on his own, completely independently. In addition, ever since he had learned about anthroposophy at 17 through a newspaper article by Friedrich Rittelmeyer, he had been reading more and more writings by Rudolf Steiner. Thus, by the time he started studying in Rostock in 1920/21, he had already become deeply engaged with theology and anthroposophy through self-study. It was under these circumstances, struggling to find the truth, that the student who was still a nobody wrote the famous Friedrich Rittelmeyer the letter provided at the end of this article. This letter describes not only Frieling’s inner state, but also that of a large number of founders. (Almost simultaneously with the letter, Rudolf Frieling sent his first essay called “The John Gospel in the Light of Expressionism” to Friedrich Rittelmeyer, as the publisher of the magazine “Christentum und Gegenwart” (Christianity and the Present Time).

At that time, Friedrich Rittelmeyer was living on the Birkwitz castle estate in Silesia recovering from his accident, and he had his wife answer the letter in way that would give the recipient courage and strength to continue his intensive studies.

While Frieling had studied in Rostock at first with Professor Althaus, among others, he was now drawn to Marburg/Lahn for the summer semester in 1921. He wrote a paper that he himself described as “non olet” (literally: doesn’t stink) about “Church Relations in Chemnitz around 1670,” which contained a chapter on Valentin Weigel. He found the material for this in the visitation files of that time that were preserved in the archives in Dresden.

In his first weeks at Marburg, Frieling had met fellow student Martin Borchart, who was also the (anthroposophical) branch leader. Then Johannes Werner Klein came to visit him in his dorm room and encouraged him to go to Stuttgart with him to attend the first theological course by Rudolf Steiner in June. Frieling followed this call. Despite being only 20 years old, he was already well prepared for the course both in terms of theology and anthroposophy. Once they had all arrived in Stuttgart, everyone gathered in a classroom at the Waldorf school for an introductory talk and a meet-and-greet. It is a commonly recalled how standoffish certain participants at first found the somewhat shy and awkward Rudolf Frieling.

From the summer of 1921 on, studies in Leipzig and the steps toward the founding of The Christian Community unfolded in tandem. Rudolf Frieling wrote at that time: “It often weighs heavily on my soul how little prepared I am, but I realize that the times demand we get started soon. I am also under no illusion that the time will ever come when I say: “Now I am completely prepared!” These sentences are characteristic not only of Frieling’s humbleness, but also of the way he energetically stepped forward to work for a known good.

From the winter semester of 1921/22 until 1924, he studied in his birth city of Leipzig while he founded the congregation with Johannes Perthel. He then did his Ph.D. on “The Reformation in Zwickau.”

One of his striking characteristics was his inexhaustible humor. A fat book of anecdotes could be written with hilarious stories and word plays. “I do not belong to the mimosa confession,” he wrote once. The first time he was meant to speak to the Leipzig congregation, it did not take long before he had already “said everything that he knew,” and the experienced Johannes Perthel had to step in and bridge the embarrassing gap. Rudolf Frieling: “We were much too young, after all. It was a children’s crusade.”

After completing his studies and his first activities in Leipzig, Rudolf Frieling worked in Mannheim (November 1924 to October 1926) and then Nürnberg. Members recalled long after the fact how they had learned Greek with him back then in order to be able to take up the St John Gospel in its original language.

In October 1927, he moved to Vienna in order to help build up the congregation until The Christian Community was banned in 1941.

He had married Margarethe Gayda on January 3, 1925, during the Berlin Convention in the Singacademie. From then on, a 45-year intimate common bond played a major role in Rudolf Frieling’s life work.

In April 1929, the office of Lenker (regional coordinator) was conferred on him, and he worked as such during the 30s in Bavaria. In 1938, Emil Bock designated him as his successor in the office of Erzoberlenker (chief coordinator). In August 1949, he became a titular Oberlenker (senior coordinator), and on February 24, 1960, he became Erzoberlenker. He then occupied this position a few years longer than Emil Bock.

While The Christian Community was banned, Rudolf Frieling at first found a position at the Vienna Antiquities and Monuments Office. “The monument that needed protecting was myself.” From November 1941 all the way into December 1945, he was deployed as a medic in Austria, in the region in which Rudolf Steiner had spent his childhood and youth. Later, he was in the vicinity of Berlin, and after the war ended, he was still in Stade as a prisoner until he was released to Marburg/Lahn, where his wife had found refuge with her parents after Vienna was occupied.

An episode reported from the beginning of the ban on The Christian Community shows Rudolf Frieling’s inner strength: A visiting colleague told him about the resigned attitude he had found among his friends during his travels. (The situation then was deadly serious.) Rudolf Frieling, slamming his hand on the table, yelled: “I don’t give a hoot about a Christian community that is blown over by the first wind. We will have to withstand very different storms still.”

After World War II, he worked out of Marburg as a “traveling preacher,” with particular focus on the congregations in the Rhein-Ruhr region, then for quite a while in Upper Bavaria, where large groups of members and friends had fled to many small towns.

In 1949, he moved to the United States, where he founded the first congregation in New York and from there was active for The Christian Community in other cities. This time lasted until 1954, after which he lived and worked in Stuttgart in the Fiechter/Bock house until he had to be entrusted to the Morgenstern House nursing home for the last two years of his grave illness. He died on January 7, 1986, at almost 85.

“An enlightened Christianity has once again become possible [through anthroposophy]. The Christian Community, on its special turf, also seeks to serve this kind of enlightened Christianity.”

A profound student of anthroposophy, Rudolf Frieling sought for enlightenment through the awakening spirit throughout his life. He was an outstanding lecturer and preacher. For almost 50 years, his classes at the priest seminary were among the most impactful student experiences. His theological works are available today in a four-volume set.

As a priest, because of his office on behalf of the priesthood (erzoberlenker), he was responsible for carrying out the sacrament of ordination. Through this, his impact extended in a special way far beyond lectures and writings to his service to the Word.

——————————————-

Letter to Friedrich Rittelmeyer, Berlin

Most Honorable Minister!

Please forgive me, a total stranger, for asking you in writing for a big favor. I realize that I am being rather importunate, to say the least, but I do not do so on a whim. After waiting for a long time, I now see no alternative but to write you.

I am a theologian; it is about Rudolf Steiner.

Perhaps it would be best for me to quickly summarize what I have been doing until now. I became interested in theology in secondary school, particularly the New Testament. After a few years, I ended up out in left field, with Heitmüller1-Bousset2-Jülicher3-(Joh. Weiss). I took this position not because I enjoyed destroying and negating, but because I believed I owed it to my sense of truthfulness, to my scientific conscience; I made many sacrifices of the intellect in the process, some of them quite painful. I was in no way inwardly satisfied. All that was left of Christianity for me was veneration for the prophet Jesus based on the radically sanitized Mark and some logia (sayings attributed to Jesus Christ), but even this basis seemed to me to waver at times under the influence of Wrede and Bruckner. The St John Gospel had a powerful impact on me, but I thought I had to deny it any historical value. Paul struck me as having very little to do with Jesus.

I became aware of anthroposophy through your article on Steiner in the Christian World in the fall of 1917. You wrote once that, of course, there were also those kinds of people who treated Steiner’s teachings as new “Catholic dogma.” Well, what is a person to do? I could not just fish out a couple of crumbs that happened to appeal to my subjective taste and assimilate them into my world view, dismissing other things that struck me as unlikely. What right would I have to do that? After all, I cannot check what the man is saying. I do not know where his infallibility stops, where the border between the objective and the subjective lies with him. Either I doubt his infallibility, in which case everything is pretty worthless for me, because then I do not have the right to fish out this or that, or I simply have to believe. I am comforted by the fact that you, as a theologian, must have grappled with all these thoughts, too. It pains me that I am unable to take a certain stand with unshakable firmness, I am jealous of professors who have the often-naive conviction that their world view is the only right one, and I often consider myself as lacking in character because I sway back and forth between one viewpoint and another. I had thought that, with the help of anthroposophy, I would finally be able to take a specific stand on religion, but the aforementioned considerations seem to have placed even that into question. I do not want to start all over again, though, so I am asking you, if you have time, to perhaps clear some things up for me, because I do not want to turn completely away from anthroposophy yet, as I had placed such great hopes on it. Until I have tried everything, I cannot decide on this new painful amputation.

I read with great interest your further remarks on this subject in “The Christian World” in 1918 and 1919, as well as in “Christianity and the Present.” They also allowed me to get over much that was off-putting in Steiner’s books, which I then began to read. A new world literally opened for me. It was as if I was rediscovering the New Testament. It was so comforting to have the religious feelings of my childhood restored to me, of course endlessly deepened and widened. The idea of Christ began to dawn on me, and with it a better understanding for Paul, for Luther, for the church in general (including the Catholic Church, which, in terms of reverence for Christ, could strike me only as incomprehensible and “unchristian”). It was truly a “pleasure to live,” especially as a theology.

The only way I could provisionally justify this swing to the right to my scientific conscience was with Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy. But then came a major step back. I read various anti-Steiner articles, including some claims that definitely burst my bubble. For example:

- that Steiner draws from the genealogies in Matthew and Luke the existence of two Jesus children. Even if you get used to this idea, there are still the consequences to deal with: Two virgin births!! Two Marys, two Josephs! I felt like cold water had been dumped over my head, and my faith in Steiner was severely shaken.

- that Christ escaped before the Passion (suggested in the report of the fleeing young man). I do not know where in Steiner this is written, but perhaps there is some misunderstanding here, because how do you explain the great weight given to the Mystery of Golgotha and the claim that Christ entered into the spiritual atmosphere of the earth at that time, if he was no longer even on Golgotha? Maybe there is an error here on the part of the reporter (Lic. Peters—Hanover, in the Sachsen church newspaper)?

- Steiner’s view of the gospels also caused me serious discomfort. What he wrote about them in “Christianity as Mystical Fact” was not clear enough for me. Were the synoptic reports, which seem to be so naïve and are so vividly alive, supposed to trace back to Mystery traditions? These thoughts are extremely hard to follow.

- Steiner’s exegesis on Christmas also struck me as highly dubious.

My whole view of things once again began to vacillate. What I learned from various Steiner disciples was of little help. They often did not seem so clear themselves. In any case, such people have not the vaguest idea of what lies on a theologian’s heart. That holds true for the following questions as well: 1) Does it not come down to self-redemption for Steiner? 2) What happened to Luther’s deep experience of sin and grace? The feeling of separation from God, or, as Rudolf Otto stresses, the mysterium tremendum? 3) Is there a personal relationship to God? I frequently encountered such objections when I came to Steiner’s defense—often not easy; the most difficult thing, at any rate, is the question of what is true? In the end, it comes down to either simply believing Steiner or not.

Do not take me for a hopeless rationalist. On the contrary! But unclarity of thought can be so terribly painful that it can also damage religious life. When, for example, the thought comes to me that everything is merely a suggestion, then that cripples my inner life. The question of what to think of Christ now is no academic doctoral question. I am tired of constantly searching and wondering. I yearn for certainty.

How can I come visit you where you live? I will admit the following: I have heard it claimed many times over the past months that your illness is the result of Steiner exercises, even that you were in a mental institution. As I was exceedingly frightened particularly by the latter claim, I turned to Prof. Merkel in Nürnberg, who was kind enough to tell me that I had been taken in by some tall tales. That made me very happy. Then there was the rumor that you had broken ties with Steiner. Naturally, this all contributed to my complete confusion regarding anthroposophy. Happily, this is not true, either (the break with Steiner).

I am no longer bothered by reincarnation and the peculiar cosmic picture, or by the nature of some Steiner followers. I am only concerned with Christology and what hangs together with that. I am familiar with what you wrote to rebut Johannes Müller and Gogarten. The worst thing for me right now is the business with the two Jesus children, particularly the consequences of this, a terrible scandal; the escape from the passion of Golgotha; the view of the gospels; the issue of self-redemption; sin; and the personal relationship to God (an abyss separates meditation from prayer!)…

I do not get very far with the little bit said in “Christmas,” the “Lord’s Prayer,” and “Christianity as Mystical Fact.”

So, as I said, I would like to join the Steiner movement, but I find it impossible for the aforementioned reasons, at least temporarily. On the other hand, I already have too much to thank anthroposophy for to simply tuck it away on a shelf with a light heart. That would throw me back into uncertainty.

Sending you heartfelt wishes for a speedy recovery and I again beg your pardon for my forwardness.

Rud. Frieling

_______________________

1 German Protestant theologian

2 German theologian and NT scholar

3 Professor of Church History and NT Exegesis, at the University of Marburg