← BACK

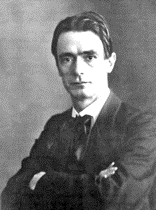

In September of 1922, a group of 45 courageous, devoted, and enthusiastic people – both men and women – were gathered together in Dornach, Switzerland. There, with the help of Rudolf Steiner, the inaugurator of modern spiritual science or Anthroposophy, the events took place which led to the founding of what we have come to know as The Christian Community.

In September of 1922, a group of 45 courageous, devoted, and enthusiastic people – both men and women – were gathered together in Dornach, Switzerland. There, with the help of Rudolf Steiner, the inaugurator of modern spiritual science or Anthroposophy, the events took place which led to the founding of what we have come to know as The Christian Community.

For just a year and three months they had been meeting, planning, and seeking for a way to renew religious life. It was poignantly felt that one could not authentically pray and experience the Spirit in the traditional forms anymore. Many of them had been through the trench-warfare and destruction of the first World War and came home to a spiritual life that was bankrupt in the face of such horrors.

Although most of them were under 30 (Emil Bock was 28, Rudolf Frieling was 21) all of them, young and old, had come to recognize the spiritual giant who could lead them to the wellspring and source of religious renewal: Rudolf Steiner (27 February 1861 – 30 March 1925).

Alfred Heidenreich, who pioneered the work of the Christian Community in England, North America and South Africa, tried to express what Rudolf Steiner meant to the movement in his moving and personal book on the events surrounding the founding titled, Growing Point:

“The significance of Rudolf Steiner for Christianity is not confined to the foundation of The Christian Community. He was himself, simply as a being, an event in the history of Christianity. In the memorial article which Dr. [Friedrich] Rittlemeyer [first leader of the religious renewal movement and one of the most well-known Lutheran ministers in his day] wrote after Rudolf Steiner’s passing…:

’In earlier ages, the fact alone that such an all-embracing genius gave witness to Christ as being the greatest reality in earthly history, would have had a profound effect.

But in Rudolf Steiner much more was present. One could put it like this: he comprehended all branches of learning so spiritually and so deeply, and he recognized Christ in such big and broad dimensions that eventually Christ shines forth as the true light in all spheres of life. He observed strictly the necessity for each sphere to form its own method according to its intrinsic laws. He never carried religion into anything from without. But he illuminated all realms of knowledge with such powerful light, that Christ became visible in it. A Christ, it is true, far greater than the Christ of the Churches; but a Christ related to the Bible and to the Christ of the early Christians.

Thus he advanced the science of language to the point where it could understand why Christ is called ‘the Word’. Thus he carried medicine to the point where medicine could understand again ‘the body of Christ’. Thus he carried astronomy to the point where Christ became visible as the true ‘Light’…he taught how science could again become reverent and devout. He built a temple for all sciences, so high and so broad, that their servants could work in it without sacrificing an iota of their personal freedom or of the special characteristics of their province. He united the learning of the age with Christ, and Christ with the learning of the age.’

Rittelmeyer’s description opens up a vista for the future. The condition of the Middle Ages when Church and civilization were identical is not likely to be repeated. If it were, it would be a relapse into a past phase of evolution. We must move towards a future where Christianity and civilization become identical; where the very methods of scientific research will be Christian, and where it will be felt that what is not Christian is not scientific.

In this civilization the ‘Church’ will have its special place. Like the mother whose children have grown up and become independent, the Christian Church of the future will be able to concentrate on its particular task. It will practice the personal meeting with Christ as a Being.

Heidenreich reveals the most important aspect of this founding in this last sentence above. It was not a startling new teaching or religious philosophy that was formulated. If that were the case, our movement would long have faded away. No, at the beginning of a new Christian priesthood and sacramental stream stands an event: On September 16th, 1922, the first “Consecration of the Human Being”[1] was celebrated by Friedrich Rittelmeyer, and in that moment the movement was granted the grace to work in Christ:

“…The event was astounding. But the reality was as plain as a sunrise. You do not dispute the sun. You bow to its rays” (Heidenreich).

This experience became the bedrock of the founders’ ability to proclaim Christ, for they had experienced him. It was not an abstract theology but an experience of the divine in the ritual that became the foundation for their and all future work in The Christian Community.

-Rev. Patrick Kennedy, priest and seminary director in North America (Toronto, Canada)