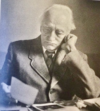

Hermann Beckh

Die Gruender der Christengemeinschaft: Ein Schicksalsnetz

By Rudolf F. Gaedeke

Translated by Cindy Hindes

Hermann Beckh

May 4, 1875, Nuremberg – March 1, 1937, Stuttgart

When Hermann Beckh received a visitor in the last days of February 1937 at his death bed in his parlor in Stuttgart’s Lichtensteinstraße No. 10, he said as a greeting: “…. please be quiet! Dying is happening here.” This saying is characteristic of his life, not only superficially because his utterances were often original, but because a main motif of his being was the search for life beyond death.

This does not seem to be self-evident. At first, his biography predominantly showed the fullness of the original forces of being human. Throughout his life, he was often like a child. Opposing forces fought at the bottom of his soul.

Born on May 4, 1875, into a well-to-do family in Nuremberg, Hermann Beckh grew up together with his younger sister ‘Mariele’ in a carefree childhood. The formative experiences of his first years were shaped by the flowers, the animals and stones, the weather, and the stars. His parents’ travels to the Tegernsee and Berchtesgaden regions and to the Allgäu enabled him to breathe deeply in his childhood soul. In the fourth year of life (1879), this led so far that a rapture state occurred. The impression of the high mountain world near Einödsbach (Allgäu) overwhelmed his consciousness: “I am sure that many people never experience anything of what I experienced there ‘on the other shore of being.’ It was the world of my prenatal existence, … which I had forgotten. ” This is how Hermann Beckh described this experience in his memories of childhood.

When he had to go to school, he felt that this was a ‘violation and deprivation of freedom.’ He didn’t understand why such methods were used when he was able to recite a page-long prose text by heart after reading it once. For years he studied as if in a dream. Languages especially were not difficult for him, so he eventually learned fourteen languages through his later studies. Only in the further school years did the painful necessity arise for him to work more systematically and with diligence. The ‘Gymnasiumabsolutorium,’ the Abitur, was then passed with flying colors. The written examinations had gone so well that oral ones were ordered. This qualified him for a place at the Maximilianeum in Munich.

If the Nuremberg Abitur fell in the year 1893, the study of law, for which Hermann Beckh strangely decided, lasted until 1896 and his time as an assistant judge until 1899. During this time (1899), it happened that he had to sentence a poor married couple with a child for wood theft. Because with a prison sentence, the child would have remained alone, Hermann Beckh sentenced the couple to a fine. But because the couple had no money, Hermann Beckh gave them the sum out of his own pocket after the sentence was passed – and resigned from his post.

Then he began to study anew. To access the sources of human culture, he learned Sanskrit, Tibetan, Indian, Persian, Egyptian, and Hebrew. He studied in Kiel and Berlin, where he received his doctorate from the Humboldt University in 1907 and qualified as a professor in 1908. He became the authority on ancient languages of the Himalayan region and was the first to translate many texts of that region from ancient manuscripts in the Prussian State Library. If he was thus close to the sources and origins of human culture, the second great area of death experience also emerged. He had loved the mountains since his childhood. Once, while hiking in the high mountains, he got caught in a dense fog. He spent a whole night on the edge of a glacier, his feet stuck in his backpack, fighting frostbite. When he was twenty-nine years old, his grandfather died (1904) – the first death in his immediate environment. During the First World War, he only had typing duties in Romania and Bulgaria, also in Kiel and Berlin. Death only really struck him closer when, fifteen years after his grandfather, in 1929, his beloved sister Marie, who had always faithfully accompanied him, died. The mother survived both children and died on May 25, 1943. (No date of the father’s death has been handed down.)

Hermann Beckh

In 1911, when Hermann Beckh was 36 years old, he met Friedrich Rittelmeyer as well as Rudolf Steiner. Since he had already become acquainted with Indian theosophy, he now found in anthroposophy the spiritual bond of all the cultural-historical studies he had pursued up to that time. Now the connection of the history of consciousness of humankind, as it also shows itself in the history of languages, became clear to him. With the two volumes of the Göschen Collection on Buddhism, published in 1916, he began his real life’s work (see the list of writings), which he developed as a speaker, university teacher, and writer.

In addition to his work on the early cultures of humankind, which gave rise to From the World of Mysteries, Hermann Beckh had been deeply involved in music since childhood. At the age of sixteen, he experienced Richard Wagner’s Parsifal in Bayreuth in 1891. The last of Beckh’s works, completed on his deathbed, was Die Sprache der Tonarten (The Essence of Tonality). He had also felt connected to the starry world from an early age. A rich work, “Beiträge zur geistigen Sternenkunde,” (Contributions to Spiritual Astronomy) was dedicated to his fellow pastors in their Rundbrief (newsletter).

The fruit of Beckh’s studies on Buddhism

His two books about the cosmic rhythms in Mark’s Gospel and John’s Gospel should be mentioned especially. They would demonstrate from the spiritual science that the cosmos order and earthly working of Christ belong together.

In Karlsruhe, a philosophy professor, Arthur Drews, had written the book Die Christusmythe (The Christ Myth), in order to show that the Gospels contained nothing but mystical-fairy-tale illustrations of star processes (astral myths). This Arthur Drews belonged to the ‘Combat League against Anthroposophy’ and had expressed: “My I shall be taken by the devil after my death,” and his gravestone read: “Redemption is a detachment from the I.” Against the pantheistic religious philosophy of Arthur Drews, Beckh’s aforementioned works were meant as positive aids to understanding the Gospels.

Hermann Beckh

The always childlike admirer of all that is high and noble, who nevertheless possessed intellectual abilities in abundance, the shrewd jurist, the profound explorer of the word, and the harmonies of the starry and tonal world reaped the fruits of his labor in abundance. Nevertheless, in his opinion, he lacked the real thing. When the preparations for the foundation of the Christian Community had already led to the first two teaching courses with Rudolf Steiner, Professor Beckh had not been asked to collaborate. He had been the anthroposophical speaker at the opening of the first Goetheanum building in 1920. Rudolf Steiner had said of him: “He has done a lot of research that I have not yet come to, although some of it is somewhat speculative.” Hermann Beckh was regarded as an outstanding expert who was not asked for new activity after he had given up his university work to serve Anthroposophy.

He heard about the preparatory group that met in March 1922 in Friedrich Rittelmeyer’s confirmation hall and appeared there with the vehement words: “Now I am here and belong to you; and even if you don’t like it, you won’t get rid of me! ” Thus he became a priest of his own will, a servant of the word in an even more comprehensive sense than before.

As a co-founder of the Christian Community in Stuttgart, he was also its teacher from the beginning. He had become acquainted with anthroposophy in 1911 through an Elijah lecture, but now he himself worked with the firepower of his will for the Word like Elijah. In December 1923, he attended the Christmas Conference for the founding of the General Anthroposophical Society at the Goetheanum in Dornach.

Hermann Beckh

He was also the lovable-scattered, shy, yet child-loving professor who, somehow not quite present, often seemed clumsy and tempted ridicule. He was lonely in the founding community. He remained misunderstood and knew that he had to “persevere in resistant circumstances.” His severe kidney cancer forced his soaring spirit through pain to the body: “dying is happening here.” But looking to the future, he had written in a poem about the New Jerusalem:

“And even if my path still leads over graves,

Even if I must still be a bearer of death,

There shines on the path from the world’s farthest reaches

the resting star’s holy serious light.”

As a seminary teacher, Hermann Beckh had imparted to a whole generation of priests the enthusiasm for the spiritual work with the word, the language. The Christian Community preserves his work in the cultural sphere, where his renderings of Genesis 1 – “In the Spiritual Thought of the Original Beginning” and of the 23rd Psalm – “He who speaks the I in me is my shepherd…” – are read again and again on the occasion of larger sermons.

Caption for Picture:

The fruits of Beckh’s studies on Buddhism

The reflections in Schultze Naumburg’s magazine Kunstwart gave rise to interest in and questions about art. Friedrich Naumann, the theologian who became a politician, awakened Pauli’s interest in politics. In theology, which had hitherto been the content of his studies, historical interest in Jesus awoke, and Christ as the Son of God disappeared from consciousness. “At that time, the path had to be taken from the dogmatic Christ, who no longer had any life in him for us, to the historical Jesus.” It was as if, at a later point in the unfolding of his life, something came to light that others had experienced earlier. August Pauli was a loner. He also took his inner steps basically in melancholy solitude and without a friend.

The reflections in Schultze Naumburg’s magazine Kunstwart gave rise to interest in and questions about art. Friedrich Naumann, the theologian who became a politician, awakened Pauli’s interest in politics. In theology, which had hitherto been the content of his studies, historical interest in Jesus awoke, and Christ as the Son of God disappeared from consciousness. “At that time, the path had to be taken from the dogmatic Christ, who no longer had any life in him for us, to the historical Jesus.” It was as if, at a later point in the unfolding of his life, something came to light that others had experienced earlier. August Pauli was a loner. He also took his inner steps basically in melancholy solitude and without a friend. mere farming village, it was prosperous and knew how to maintain this prosperity with firm social forms, right up to marriage. The parish priest was an integral part, indeed the guarantor and often the enforcer of the customs and laws of old. The new pastor had questions everywhere, challenged the customs: Should this be Christianity? Is it not rather Old Testament, pre-Christian? Is a people’s church at all capable of being Christian? Doesn’t the uniformity of a community contradict spontaneous enthusiasm, the filling of the individual with the spirit? “O could I, like Paul, be a carpet weaver and then, when I wanted to, not if it drove me, if it were an inner necessity for me, help my fellow men come to the truth, to God – would that not be the better, I might say purer in style and therefore a more effective way to serve the cause of Jesus?” Thus wrote August Pauli in his book Im Kampf mit dem Amt. Erlebtes und Geschautes zum Problem Kirche [Struggling with the Office. Experiences and Observations with the Problem of the Church] (1911, p. 47), which was probably significantly influenced by his experiences in Westheim. He could “do nothing but faithfully guard their [the church’s] sleep.”

mere farming village, it was prosperous and knew how to maintain this prosperity with firm social forms, right up to marriage. The parish priest was an integral part, indeed the guarantor and often the enforcer of the customs and laws of old. The new pastor had questions everywhere, challenged the customs: Should this be Christianity? Is it not rather Old Testament, pre-Christian? Is a people’s church at all capable of being Christian? Doesn’t the uniformity of a community contradict spontaneous enthusiasm, the filling of the individual with the spirit? “O could I, like Paul, be a carpet weaver and then, when I wanted to, not if it drove me, if it were an inner necessity for me, help my fellow men come to the truth, to God – would that not be the better, I might say purer in style and therefore a more effective way to serve the cause of Jesus?” Thus wrote August Pauli in his book Im Kampf mit dem Amt. Erlebtes und Geschautes zum Problem Kirche [Struggling with the Office. Experiences and Observations with the Problem of the Church] (1911, p. 47), which was probably significantly influenced by his experiences in Westheim. He could “do nothing but faithfully guard their [the church’s] sleep.” But the political orientation of the church was also intolerable to August Pauli. On the birthday of the emperor (January 27, 1918), the superintendent held the sermon with the theme: “The Hohenzollerns are given to us by God for wisdom and for justice and for sanctification and for salvation.” So his friend Christian Geyer’s offer to take up a pastorate in Nürnberg fell on good ground. But the church leadership did not want to see him in Nürnberg. So he went to Regensburg (December 1918). Even though the people in this southern German city were more accessible and open, church life again shaped itself in the old traditional forms. “I was obviously not yet in the right stream.” In 1921/22, the ‘Leimbach case’ occurred in the Bavarian Regional Church. Pastor Leimbach in Öttingen was a militant advocate of a radical-modern theology. Bavaria’s pastors were divided over him when he was to be suspended. Dr. Christian Geyer, at the head of about fifty modern-minded colleagues, took a six-month leave of absence. In view of the founding of The Christian Community, which Geyer helped to prepare, he hoped to be expelled from the church. This did not happen, and Geyer travelled back to Ansbach to the General Synod instead of Breitbrunn and Dornach.

But the political orientation of the church was also intolerable to August Pauli. On the birthday of the emperor (January 27, 1918), the superintendent held the sermon with the theme: “The Hohenzollerns are given to us by God for wisdom and for justice and for sanctification and for salvation.” So his friend Christian Geyer’s offer to take up a pastorate in Nürnberg fell on good ground. But the church leadership did not want to see him in Nürnberg. So he went to Regensburg (December 1918). Even though the people in this southern German city were more accessible and open, church life again shaped itself in the old traditional forms. “I was obviously not yet in the right stream.” In 1921/22, the ‘Leimbach case’ occurred in the Bavarian Regional Church. Pastor Leimbach in Öttingen was a militant advocate of a radical-modern theology. Bavaria’s pastors were divided over him when he was to be suspended. Dr. Christian Geyer, at the head of about fifty modern-minded colleagues, took a six-month leave of absence. In view of the founding of The Christian Community, which Geyer helped to prepare, he hoped to be expelled from the church. This did not happen, and Geyer travelled back to Ansbach to the General Synod instead of Breitbrunn and Dornach. opened his soul to his fellow human beings in radiant mildness, and the refined humor of old-age wisdom met his friends. From that time on, August Pauli was able to perceive clear experiences from beyond the threshold, from the so-called dead, with an alert daytime consciousness. With this ability, he was able to help many people in the following difficult years of prohibition and war.

opened his soul to his fellow human beings in radiant mildness, and the refined humor of old-age wisdom met his friends. From that time on, August Pauli was able to perceive clear experiences from beyond the threshold, from the so-called dead, with an alert daytime consciousness. With this ability, he was able to help many people in the following difficult years of prohibition and war.