Johannes Perthel – September 9th, 1888 – July 20th, 1944

Die Gruender der Christengemeinschaft: Ein Schicksalsnetz

By Rudolf F. Gaedeke

Translated by Gail Ritscher

September 9th, 1888 Leukersdorf/Erzgebirge – July 20th, 1944 Friedrichshafen/Lake Constance

According to all his friends, Johannes Perthel was taken far too early from his life and work for The Christian Community. In a strange twist of fate, he lost his life in a bombing raid on Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance, where he had traveled for a vacation.

Despite a kind of cloud hanging over his destiny, those in his circle, particularly his colleagues, treasured the radiant humanness that he had wrested from his life.

The way he himself described it, ever since childhood he had always experienced himself if not quite like an outsider, then still as different, and he therefore kept to himself.

Born on September 6, I888, in Leukersdorf/Erzgebirge, he grew up in a very strict and traditional parish house. He disliked school and had no friends there. Already in elementary school, he wrote in an essay about wanting to become a pastor, and after graduating high school he studied liberal theology. He literally had to wrangle permission from this traditional father to spend the semester in “liberal” Marburg.

During semester breaks at home, he and his father quarreled constantly. His mother said nothing. Johannes became increasingly withdrawn. New forces needed to be extracted from family tradition.

Although he became a member of the national, anti-Semitic “German Student Association,” at 22 he wrote a positive review of a lecture by the Jewish Social Democrat Bernstein for the association’s magazine. Once again, he had shocked his friends.

Johannes Perthel passed his theology exam before the First World War and he fulfilled his one- year mandatory military service. During that time, however, an inner struggle caused him to withdraw from an officer candidate’s course after the first 6 months. Once again, he was totally misunderstood.

After the war began, an inner sense of duty—he had just become a pastor—made him encourage his colleagues in Saxony to take up arms for the fatherland. His best friend answered this call and fell shortly thereafter. Johannes Perthel himself was not called up and was used as a field chaplain only for the last year and a half of the war. He found this task extremely difficult both inwardly and outwardly, but he gained a great deal of important insight into the destinies of soldiers.

In May 1915, Johannes Perthel married Mechthild Grohmann, the sister of the famous Goethean botanist Gerbert Grohmann. The couple had three children.

In typical Perthel style, after his time as auxiliary pastor he chose a pastorate that required a pioneer spirit. The small Saxon mining town of Oberwürschnitz, between Zwickau and Chemnitz, had just become an independent parish. There was neither church, nor community room, nor parish house, nor congregation. Perthel reported humorously about how he managed to acquire a parish house and community room. The congregation, however, just would not coalesce. The locals were largely taciturn, hard-working miners.

Johannes Perthel now attempted to bridge the gulf between his work-world and the church. He became a member of the Social Democratic Party, again shocking his colleagues, friends, and family. Even harder to swallow, however, was the realization that the gap between workers and church was not bridgeable, even though the Saxon workers now often invited the Social Democratic pastor to give lectures.

The most valuable experience in all this was the complete inner freedom from all previous obligations, for in his social class, a Social Democratic pastor was treated like a leper.

It was under these circumstances that a friend introduced him to a young man from the youth movement, presenting him as the representative of a new world view (Weltanschauung). It was the spring of 1920, the same time that the very first request went to Rudolf Steiner for a new religious practice.

Johannes Perthel and his wife purchased Rudolf Steiner’s “Basic Issues of the Social Question” and “How to Know Higher Worlds.” Understanding what was written there came only gradually, but it was inspirational. Later, Johannes Perthel would suffer a severe shock to the system from this first introduction to anthroposophy, but for now the first step had been made. He met Rudolf Steiner in Chemnitz and learned about the preparations for religious renewal.

From this moment on, Johannes Perthel knew that he wanted to join in the work. It was soon very obvious to him that the renewals Rudolf Steiner had proposed to the founder circle would find no place in the existing church. He wished to set to work establishing independent congregations in the Ore Mountains. This became clear to him during an inner struggle in the fall of 1921, when he was attending the theological course in Dornach. According to his own account, it was thanks to his wife, who was with him in Dornach, and to the construction of the first Goetheanum that he was able to overcome “the intellect man” (Kopfmensch), as he called it. The sense impression of the large columns of the Goetheanum hall, each different and yet emerging from and connected with one another, was a decisive help.

Perthel gave up his parish in 1922 and was present in Breitbrunn. During the actual founding deeds in 1922, Rudolf Steiner had himself suggested a lenker position for Perthel. And so, on September 16, 1922, he was ordained as a priest by Friedrich Rittelmeyer during the first Act of Consecration of the Human Being.

He then established the congregation in Leipzig with Rudolf Frieling, and from there he supervised as lenker the founding of congregations in Saxony, Thüringen, and Silesia. He worked in Breslau from 1926 through the 30s, and up until the ban of The Christian Community in 1941. He was part of The Circle of Seven from the very beginning and, as such, he played a significant role in building up and initially forming The Christian Community until it was banned.

On June 9, 1941, as the ban was coming into effect, Perthel participated in the lenker meeting in Erlangen. His two daughters in Breslau came under intense pressure from the Gestapo. They were forbidden to inform their brother in the field. Perthel lived through the time of the ban as a bookkeeper for the company of a Breslau congregation member.

Although Perthel is not known for writing anything of great length, from year one of the magazine first called “Tatchristentum” his articles and reports appeared every year, as well as in the “messages” for the member, which he issued as of 1936.

Perthel worked as a lecturer, particularly during the large conferences that took place then throughout Germany, often several times a year. But it was primarily his humanity, won through much suffering, that earned him great respect and gratitude in the priest circle and among all members.

In the summer of 1944, Johannes Perthel was staying in Oberstaufen in the Allgäu visiting Elfriede Straub, the renowned community helper from first Breslau then Stuttgart. From there, he went to visit his sister-in-law, the wife of Gerbert Grohmann, as well as Marta Heimeran in Horn on Lake Constance. As the train pulled into the station at Friedrichshafen on July 20, 1944, there was an air raid alarm. All the passengers were forced to exit the train for a nearby above ground air raid shelter. It received a direct hit. There were no survivors. Days later, Elfriede Straub searched for her missing guest in Friedrichshafen. She found Perthel’s passport, riddled with holes, in a laundry basket at the police station. His memorial stone is located in a large communal burial site. He was ripped from his life not knowing that his son had preceded him, falling in the field in Russia on July 13.

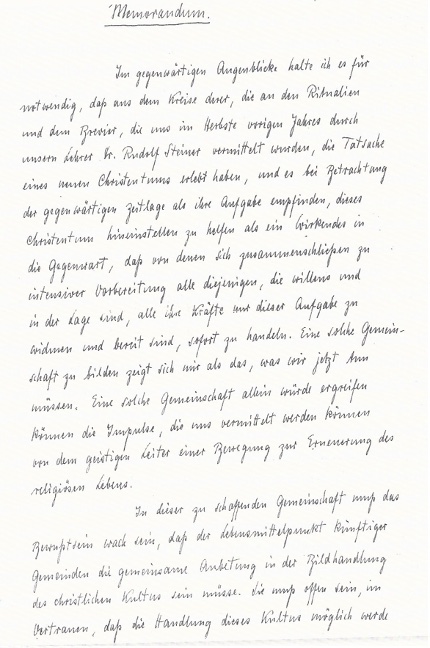

Memorandum

Oberwürschnitz, February 21, 1922

It seems clear to me from recent experiences that bringing about religious renewal in the church in the sense we mean will be impossible. To remain viable in the present, and faced with inner emptiness, the church is forced to shift more and more into outer forms. In the process, it must enclose itself in a protective shell that will render it impenetrable to all new impulses coming from outside. Furthermore, the people we need to reach today are not to be found in church. On the contrary, one gets the impression that we are not benefitting the people who come to church today if we let the new spiritual impulse flow into the sermon. As people who still somehow draw strength from the past, they also want to be uplifted by the past. So, in the long run, we ultimately do ourselves and them no favors by chaining ourselves together.

Once we have recognized this, the moment must come sooner or later when the inner impossibility becomes an outer impossibility, and if the kind of religious activity we intend is still to have any value, it must take place outside the church in the formation of independent congregations.

Because of the enormous responsibility involved, it will no doubt be tempting to postpone this decision and to wait for stronger outer relationships and greater inner readiness, but the decision must nevertheless be made at some point. Therefore, because there will have to be a decision and because the times require something, it would be good for this decision to be made today.

I thus declare myself ready to give up my parish when the time is right and help form independent congregations. My only request is that I be allowed to bring everything to some kind of conclusion by Easter.

When I think about where to work, I think I should be able to work my way into the local mining community from neighboring Oelnitz, the center of the local suburbs. These people are finished with the past and do not yet have anything new. It would just be a matter of shaking them out of their apathy. They might be able to trust someone whom they just recently knew as a pastor.

I would be most grateful if Dr. Steiner could make the effort to unite us once again for an immediate introductory course.

Johannes Perthel

Herman Groh was a man of the world who broadened his education throughout his life. He spoke many languages and understood several more. Outwardly, Groh’s life took him first to Russia, Siberia, and Vladivostok during the First World War, and then (1928) to California for 6 months. In other words, he traveled from East to West before settling in the center, where he focused his energies. This also seems to correspond to the major inward gesture of his life.

Herman Groh was a man of the world who broadened his education throughout his life. He spoke many languages and understood several more. Outwardly, Groh’s life took him first to Russia, Siberia, and Vladivostok during the First World War, and then (1928) to California for 6 months. In other words, he traveled from East to West before settling in the center, where he focused his energies. This also seems to correspond to the major inward gesture of his life.

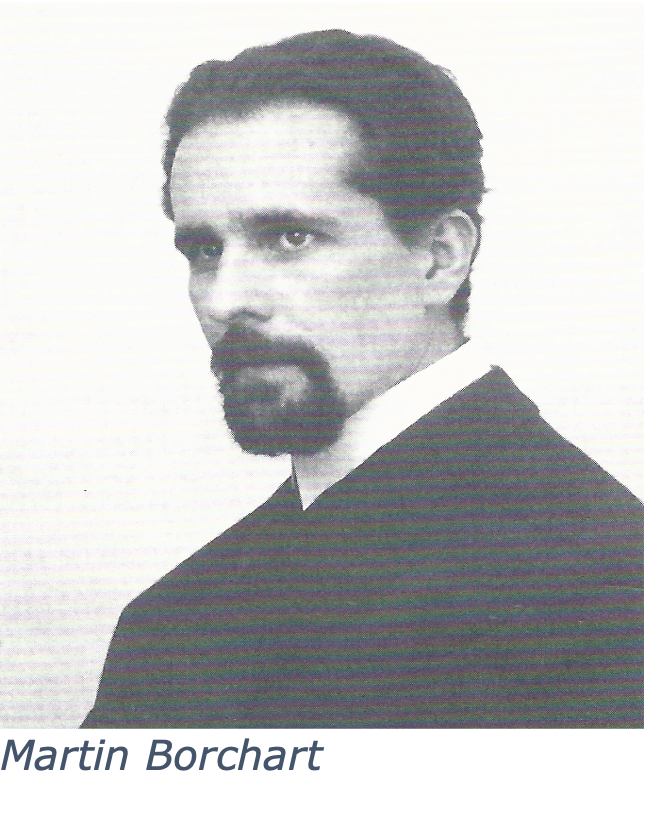

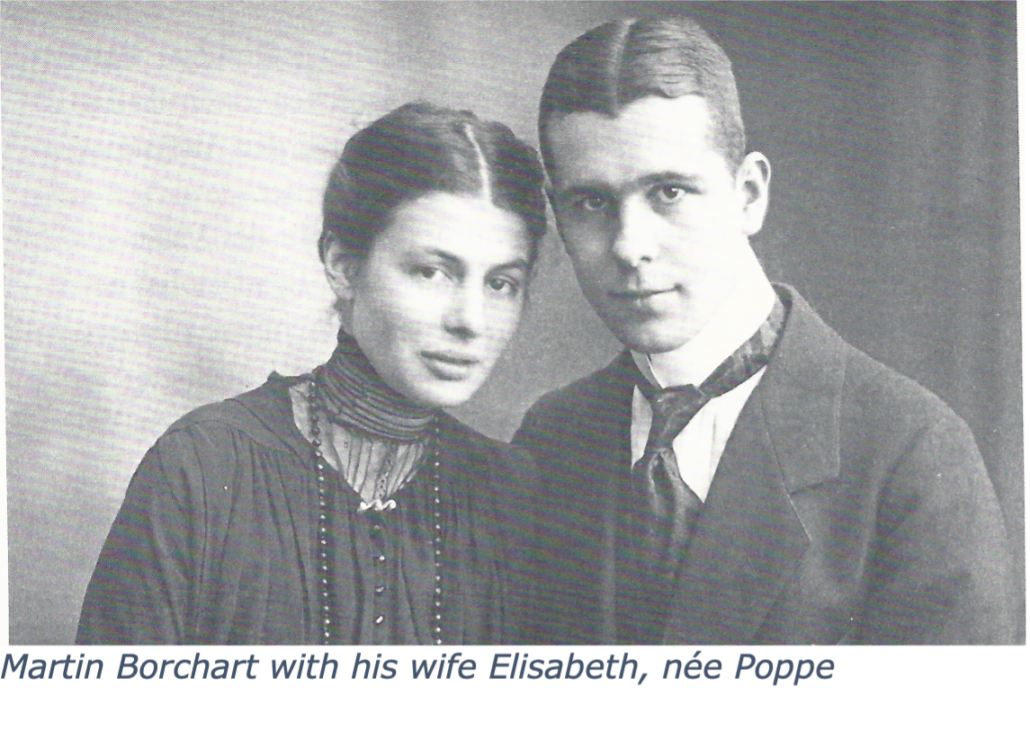

Martin Borchart

Martin Borchart one day to become his wife. On the flight from Böblingen to Heidenheim, he did not find the previously determined topographic landmarks in the actual landscape below. He had ‘flown astray’ and now tried to read the place name in a low-level flight over a train station; instead, he read Platform 1 and, on the next approach, Platform 2. After landing among fruit trees, he received information from a farmer that this was Goeppingen. The flight was continued, ending in Heidenheim, but because of adverse wind conditions, he landed on a field in whose immediate vicinity much later The Christian Community’s church was to be built. The couple in the house near the emergency landing site told him that Miss Poppe had unfortunately just left. They asked whether he knew, by the way, that she was an anthroposophist. While the housewife was already on the next topic — the abominable new invention of chewing gum in America, with which one could pull long strings out of the mouth— the master of the house enlightened the guest who had landed so rudely from the sky, “… the anthroposophists believe in the astral body”. The merchant and world traveler Alfred Meebold had written a book about it, The Path to the Spirit.

one day to become his wife. On the flight from Böblingen to Heidenheim, he did not find the previously determined topographic landmarks in the actual landscape below. He had ‘flown astray’ and now tried to read the place name in a low-level flight over a train station; instead, he read Platform 1 and, on the next approach, Platform 2. After landing among fruit trees, he received information from a farmer that this was Goeppingen. The flight was continued, ending in Heidenheim, but because of adverse wind conditions, he landed on a field in whose immediate vicinity much later The Christian Community’s church was to be built. The couple in the house near the emergency landing site told him that Miss Poppe had unfortunately just left. They asked whether he knew, by the way, that she was an anthroposophist. While the housewife was already on the next topic — the abominable new invention of chewing gum in America, with which one could pull long strings out of the mouth— the master of the house enlightened the guest who had landed so rudely from the sky, “… the anthroposophists believe in the astral body”. The merchant and world traveler Alfred Meebold had written a book about it, The Path to the Spirit. On September 16, 1922, at the age of twenty-eight, he was ordained to the priesthood by Emil Bock. He actually wanted to go to Bremen, where he had hoped for help from an uncle to found a congregation there. However, he left this city to his friend Johannes Werner Klein and became the founder of the congregation in Dresden (1922), then in Bayreuth (1924), before becoming pastor in the Stuttgart congregation in 1925, where he found the center for all his further activities.

On September 16, 1922, at the age of twenty-eight, he was ordained to the priesthood by Emil Bock. He actually wanted to go to Bremen, where he had hoped for help from an uncle to found a congregation there. However, he left this city to his friend Johannes Werner Klein and became the founder of the congregation in Dresden (1922), then in Bayreuth (1924), before becoming pastor in the Stuttgart congregation in 1925, where he found the center for all his further activities. In 1938, after Friedrich Rittelmeyer’s death, Martin Borchart was appointed Lenker for Stuttgart and the Württemberg Swabian communities. This was followed by the banning of The Christian Community by the National Socialists on June 9, 1941, and several weeks of imprisonment in the Welzheim concentration camp. During the prohibition period, he prepared for an interpreter’s examination in English and Russian in Heidelberg but, for unknown reasons, did not take the final examination. Instead, in October 1942, he joined the Stuttgart office of the Central Dairy Kuhn, Rottenburg/Neckar, as office manager, personnel supervisor, and public relations officer. During the fire in the community center in 1944, he contracted severe smoke poisoning; from then on he suffered from respiratory problems.

In 1938, after Friedrich Rittelmeyer’s death, Martin Borchart was appointed Lenker for Stuttgart and the Württemberg Swabian communities. This was followed by the banning of The Christian Community by the National Socialists on June 9, 1941, and several weeks of imprisonment in the Welzheim concentration camp. During the prohibition period, he prepared for an interpreter’s examination in English and Russian in Heidelberg but, for unknown reasons, did not take the final examination. Instead, in October 1942, he joined the Stuttgart office of the Central Dairy Kuhn, Rottenburg/Neckar, as office manager, personnel supervisor, and public relations officer. During the fire in the community center in 1944, he contracted severe smoke poisoning; from then on he suffered from respiratory problems. Heinrich Ogilvie

Heinrich Ogilvie Finally, however, he was drafted again as a guard soldier. The most important event of this second period of military service for him was his comradeship with a very simple Catholic soldier from Baden, in whom he experienced the self-evident religiosity and faith, from which he himself was meanwhile so very distant. He wrote: “In the primal goodness and love, in the freedom and irresistible truthfulness of his being, I saw the reality of Christ in a man. Now I knew that the Son of Man had lived and was still alive. Life on earth has a meaning. There is an overcoming of decadence. Gradually, I saw in more and more people that which is of Christ or what is waiting for Him. It was possible to live and work for that.”

Finally, however, he was drafted again as a guard soldier. The most important event of this second period of military service for him was his comradeship with a very simple Catholic soldier from Baden, in whom he experienced the self-evident religiosity and faith, from which he himself was meanwhile so very distant. He wrote: “In the primal goodness and love, in the freedom and irresistible truthfulness of his being, I saw the reality of Christ in a man. Now I knew that the Son of Man had lived and was still alive. Life on earth has a meaning. There is an overcoming of decadence. Gradually, I saw in more and more people that which is of Christ or what is waiting for Him. It was possible to live and work for that.”

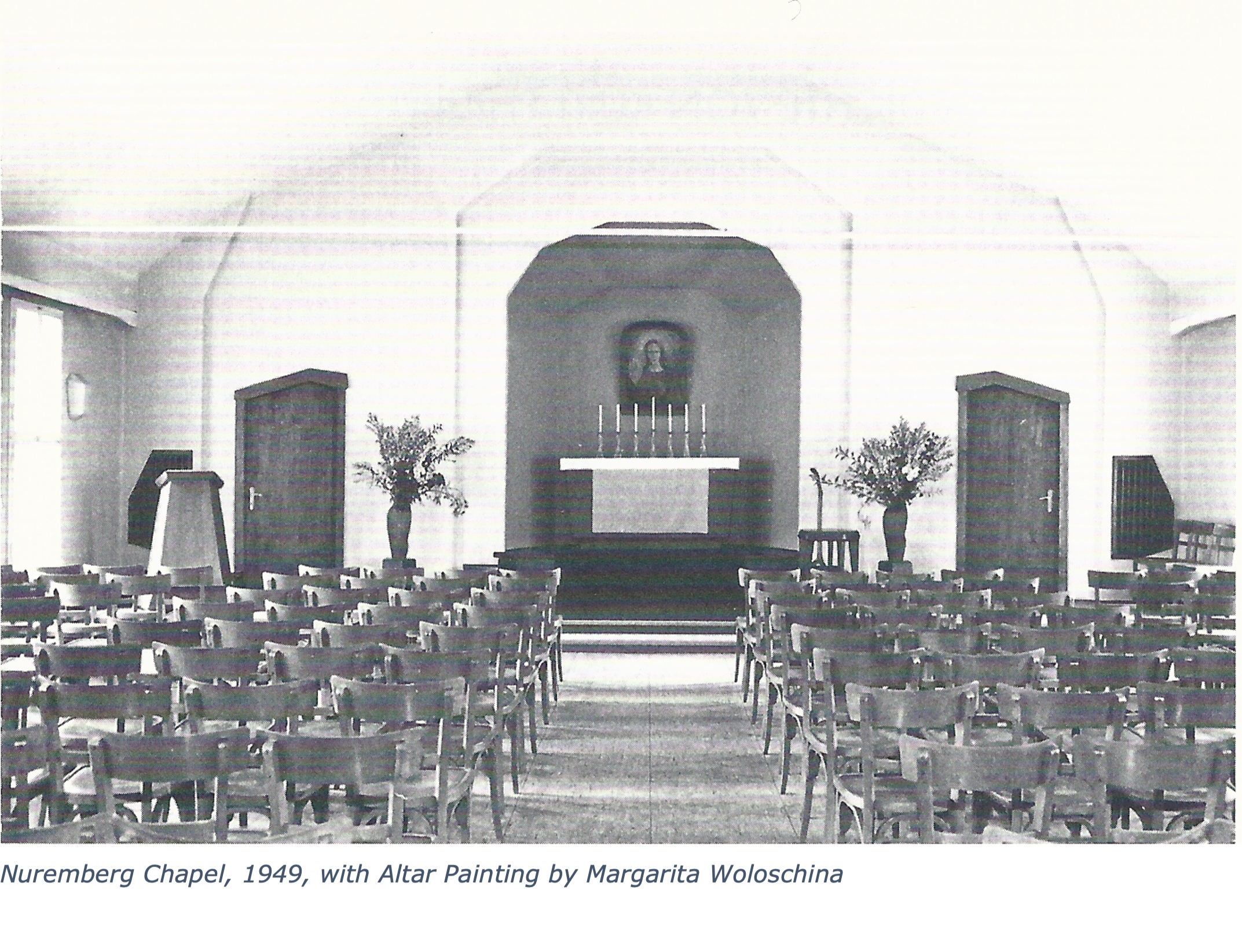

Immediately after the end of the Second World War and the collapse of the Third Reich, he began the work in the community when his colleagues could not yet be back in Nuremberg. At Pentecost 1945, the first Consecration Service after the war was read with congregation members and celebrated soon after.

Immediately after the end of the Second World War and the collapse of the Third Reich, he began the work in the community when his colleagues could not yet be back in Nuremberg. At Pentecost 1945, the first Consecration Service after the war was read with congregation members and celebrated soon after. When Otto Becher died after a severe operation in Pforzheim on July 19, 1954, another of the founders of our earthly work was lost. He was sixty-three. What he had given shone as a special color in the picture of the first decades.

When Otto Becher died after a severe operation in Pforzheim on July 19, 1954, another of the founders of our earthly work was lost. He was sixty-three. What he had given shone as a special color in the picture of the first decades. Four days after his ordination on September 16, 1922, and still during the founding events in Dornach, Wilhelm Salewski reached the age of thirty-three. He thus belonged to the middle-aged founders between the few older ones and the many very young ones. His birthday on September 20 fell on the ninth anniversary of the laying of the foundation stone for the first Goetheanum building.

Four days after his ordination on September 16, 1922, and still during the founding events in Dornach, Wilhelm Salewski reached the age of thirty-three. He thus belonged to the middle-aged founders between the few older ones and the many very young ones. His birthday on September 20 fell on the ninth anniversary of the laying of the foundation stone for the first Goetheanum building. The midwife had to navigate the flooded Elbe meadows to get to Claus von der Decken’s birth on October 5, 1888, at Preeten Castle near Neuhaus. Claus was the second of four children who were joined by a foster sister. His father, Ernst, from the old Hanoverian landed gentry, was the administrator of various estates. His mother, Anna, was born von Arnswald, whose three sisters were abbesses of the noble convents of Bassum, Medingen, and Ebstorf. Anyone who was brought into a noble convent had to have sixteen full noble great-great-grandparents.

The midwife had to navigate the flooded Elbe meadows to get to Claus von der Decken’s birth on October 5, 1888, at Preeten Castle near Neuhaus. Claus was the second of four children who were joined by a foster sister. His father, Ernst, from the old Hanoverian landed gentry, was the administrator of various estates. His mother, Anna, was born von Arnswald, whose three sisters were abbesses of the noble convents of Bassum, Medingen, and Ebstorf. Anyone who was brought into a noble convent had to have sixteen full noble great-great-grandparents. On the Eschenhof, the family had to endure difficult destinies, both humanly and in terms of health. Cécile von der Decken died in 1928, two years after the birth of her seventh child. Four years of family separation followed. The three older children moved with the Schmidt family to Kassel-Wilhelmshöhe to attend the Waldorf School. The three younger children stayed in Lübeck with their father and were looked after by his mother and sister.

On the Eschenhof, the family had to endure difficult destinies, both humanly and in terms of health. Cécile von der Decken died in 1928, two years after the birth of her seventh child. Four years of family separation followed. The three older children moved with the Schmidt family to Kassel-Wilhelmshöhe to attend the Waldorf School. The three younger children stayed in Lübeck with their father and were looked after by his mother and sister.

In addition to his work as a classroom teacher, he was soon appointed as a teacher of independent Christian religious education with the task of holding Sunday services as well. His religious groups had over sixty children! During the same period, people repeatedly turned to him – or were sent to him by Rudolf Steiner –requesting baptisms or marriages.

In addition to his work as a classroom teacher, he was soon appointed as a teacher of independent Christian religious education with the task of holding Sunday services as well. His religious groups had over sixty children! During the same period, people repeatedly turned to him – or were sent to him by Rudolf Steiner –requesting baptisms or marriages.