What is truth?

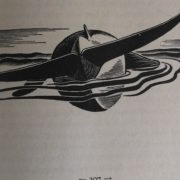

And heaved and heaved, still unrestingly heaved the black sea, as if its vast tides were a conscience.

Herman Melville, Moby Dick

The altar is a mysterious place. It renders its mysteries only slowly and in stillness. This is why the altar wants to be visited more than once. The religious experience is nourished by its repetition. Religiousness therefore roots in the essence of all things: the sun rises more than one morning; we get to know the seasons through their returning; day and night live by their alternation. The altar gathers the pathways and orbits out of which all repetition can unfold. We come to the altar, leave, and come back. This breathing of coming and going, of appearing and disappearing, gives life not only to the human but also to the divine being. In the interplay of giving and receiving, of concealing and revealing, the divine can mirror itself in the human. For what does it mean to be human? The human being shows and hides itself at the same time. We stand in the world. We live and work in it, experiencing joy and sorrow. That part of us is visible. Another part of us, though, cannot be found in this world. It remains invisible. It withdraws itself. It is there and it asserts itself, but remains removed never the less. This is our spiritual being. We carry this secret part of ourselves to the altar in the Act of Consecration of Man. In doing so, the altar becomes an image of our own being: it is both visible and veiled. It waits and is patient. It grants the fullness of its secrets only to those who return. Faith, Goethe said, is love for the invisible. It is an openness for the secret, a willingness to be addressed. This willingness to receive a revealing word, a blessing gesture, or the silence in between them, is a condition for experiencing the elusive thing that we call truth. For truth is not the mere establishing of a fact. It is not the rendering of a correct assessment or the verification of certain circumstances. Truth is much more than that. “The truth is not a fixed system of concepts that can manifest itself in only one way, but is a living ocean in which the spirit of man lives, and that can bring forth waves of the most different kind at its surface.”[1] (Rudolf Steiner)

The notion that truth is not correctness but a deep, moving force with a surface and hidden depths, opens up new possibilities of thought. The German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) was able to delve into these possibilities with pertinent skill. Versed in Greek, he let the original words speak for themselves. Truth is called aletheia in Greek. This sparked the imagination of Heidegger. Because for the good listener this means, that according to the Greek truth meant bringing something or someone out into the open. The word aletheia is a compound of the word Lethe and its negation, a. In Greek mythology the Lethe is the river that brings forgetfulness. In that respect it is the counterpart of the river Styx, that brings remembrance. Just before a human being is born, he or she wades through the river Lethe. Human beings forget the life they led before they were born. The part of ourselves that we forget about when we enter this world, is the part we leave behind. It is the part of us that remains hidden, sheltered in the spirit. When we die, we remember who we are. Dying is disclosing. We are reunited with our essence, our eternal being, and we awaken. This awakening is brought by wading through the river Styx. When truth is called aletheia, the word itself thus indicates that truth shreds all veils of ignorance. Aletheia means the vindication of what was left behind. It means the opening up of what was closed at birth. The truthful person or truthful event is therefore he or that which stands in the unconcealment (Unverborgenheit) of things. For Heidegger it became a matter of great importance not just to grasp this intellectually. He wanted to live this to the fullest of all extents. This he did in thought. It became clear to him that truth is less like a field of stones and more like water. He crossed and followed the Lethe and the ocean of Being opened up to him…

[1] GA 6 Goethes Weltansschauung, Kapittel 1, Persönlichkeit und Weltanschauung.

This post is from an article published in the spring 2018 issue of Perspectives, and can be found in its entirety with the editor’s permission here. To subscribe to Perspectives, and receive issues via email, please visit their site.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!