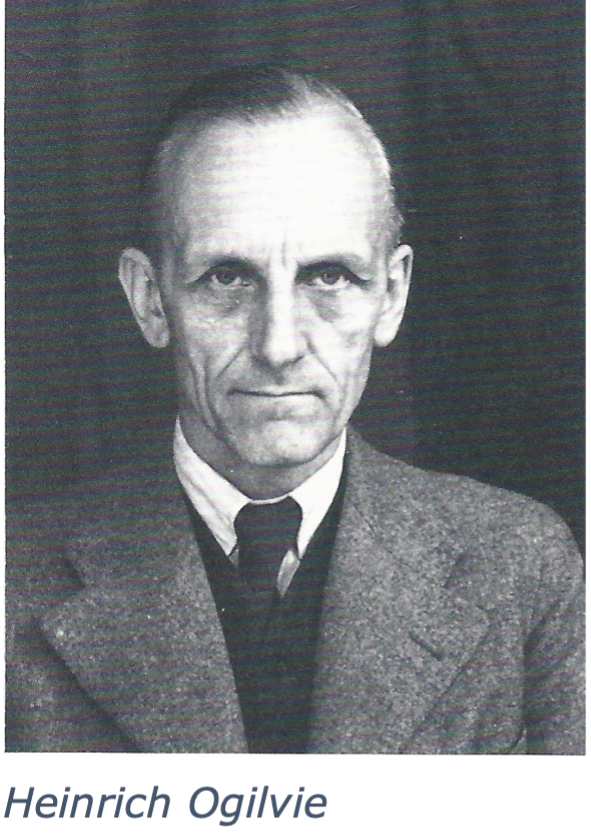

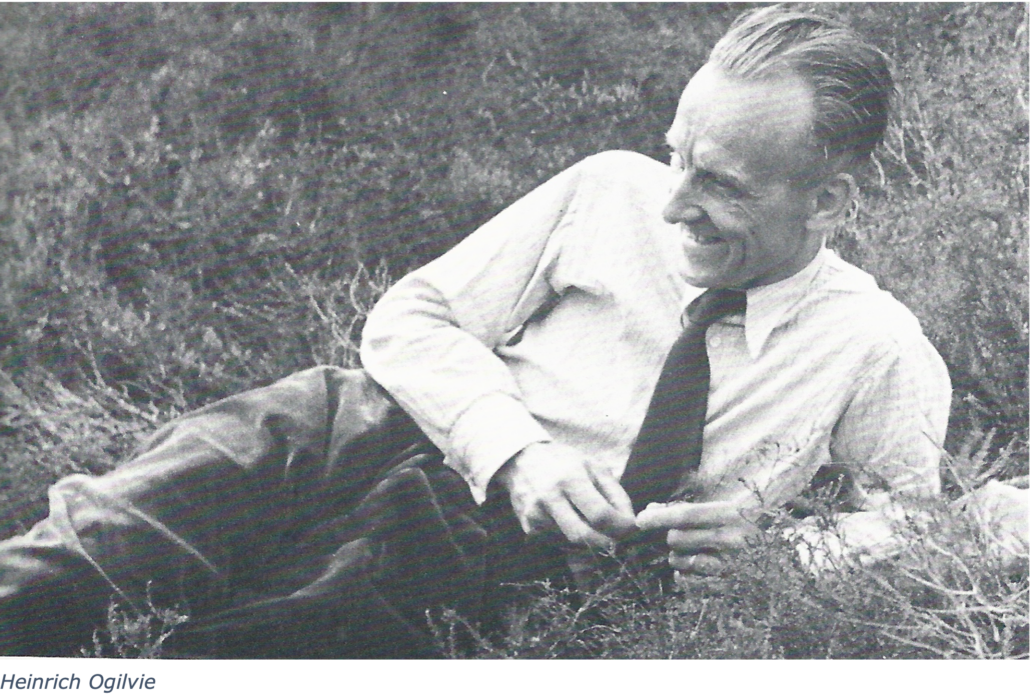

Heinrich Ogilvie

Die Gruender der Christengemeinschaft: Ein Schicksalsnetz

By Rudolf F. Gaedeke

Translated by Cindy Hindes

Heinrich Ogilvie

Heinrich Ogilvie

July 18, 1893, Schleusingen – February 15, 1988, Zeist

Heinrich Ogilvie’s father was supposed to have taken over the administration of at least one of the family estates in the Memelland. For this purpose, he had studied and graduated in law. However, shortly after he took over the administration, he voluntarily renounced his inheritance in favor of his younger brother, who did not yet have a profession. He then became a lawyer in the small Thuringian town of Schleusingen and married the daughter of the local high school principal.

Heinrich Ogilvie was born in Schleusingen on July 18, 1893, the third of eight children. Two siblings died early. As the eldest surviving son, Heinrich Ogilvie received a particularly strict upbringing in keeping with family tradition. A weakness in the little child’s back caused the doctor to prescribe a two-year bed rest treatment. The boy was also often sick, and, in some cases, had repeated childhood illnesses. He was so weak in elementary school, that he was considered a dreamer and was tormented by his comrades. For example, they repeatedly pressed him crosswise against a wall. Finally, on one such occasion, he managed to stage a powerful outburst of anger, with which he was able to send his classmates fleeing.

In him, who on his father’s side came from an old Scottish noble family, there lived an overpowering soul of will, but also of passions, as he himself described it in the small booklet of his memoirs, Jakob, wo bist du [Jacob, Where Are You]?

He fared better in high school. The teachers and the subject matter didn’t appeal to him very much, but the circumstances seemed more humane because the director was his mother’s grandfather.

An overwhelmingly painful stroke of destiny came into his childhood life with the news of his mother’s death, which reached the twelve-year-old Heinrich during summer vacation on the island of Föhr. Now the world of childhood perished, and another world appeared on the horizon of consciousness. He wanted to turn toward it. Now it was clear to him: I want to become a pastor! Every Sunday, he went to the Lutheran church with his grandfather. But after age fourteen, distress, doubts, and the passions of the “wild blood” of the ancestors increased in his soul.

For a year, the fifteen-year-old was preoccupied with Lenau’s epic The Albigensians with its impressive description of the so-called heretics. At sixteen, he was fascinated by the Epistle to the Galatians from the New Testament because he found in it the motif of the freedom of human conscience as he understood it. In the same year, however, his beloved and revered grandfather was snatched from him (1909). It was the second death in his young life that marked his soul.

Now Heinrich founded a literary students’ association. He read poems — on one evening, for example, by Goethe – but not before he had read all of Goethe’s poems for himself and selected those that were important to him. Schiller’s dramas, as well as many others, were treated in the same way. The young man had now become also physically stronger. He practiced a lot of sports: gymnastics, competitive swimming, and soccer.

In 1911 at eighteen, Heinrich Ogilvie graduated from high school and immediately began to study theology (in Halle an der Saale, among other places). He also read philosophy, psychology, politics, and art history. However, doubts about everything that had been handed down, ignited by an article by Johannes Müller (“Glaube und Wissen” [Faith and Knowledge]), pressed him hard. But when the World War broke out in 1914, he hoped to escape this world of doubt and bleak meaninglessness by dying in a hail of bullets.

A third time he looked death in the eye: it was a wound he had to endure. A sniper’s bullet had shattered his thigh while he was transporting a wounded comrade. After eight months in the hospital, the twenty-one-year-old had to learn to live with the fact of his disability. Nevertheless, he was able to take his theological state examination during this time.

Finally, however, he was drafted again as a guard soldier. The most important event of this second period of military service for him was his comradeship with a very simple Catholic soldier from Baden, in whom he experienced the self-evident religiosity and faith, from which he himself was meanwhile so very distant. He wrote: “In the primal goodness and love, in the freedom and irresistible truthfulness of his being, I saw the reality of Christ in a man. Now I knew that the Son of Man had lived and was still alive. Life on earth has a meaning. There is an overcoming of decadence. Gradually, I saw in more and more people that which is of Christ or what is waiting for Him. It was possible to live and work for that.”

Finally, however, he was drafted again as a guard soldier. The most important event of this second period of military service for him was his comradeship with a very simple Catholic soldier from Baden, in whom he experienced the self-evident religiosity and faith, from which he himself was meanwhile so very distant. He wrote: “In the primal goodness and love, in the freedom and irresistible truthfulness of his being, I saw the reality of Christ in a man. Now I knew that the Son of Man had lived and was still alive. Life on earth has a meaning. There is an overcoming of decadence. Gradually, I saw in more and more people that which is of Christ or what is waiting for Him. It was possible to live and work for that.”

After the end of the war, he took over the leadership of a kind of student residential community, the “Tholuk-Konvikt” in Halle an der Saale. In 1919 he passed the first and, in 1921, the second examinations and was thus a candidate for the ministry. But he did not want to take on a pastorate. He wanted to be socially active. In fact, he wanted to renew the whole of culture. He founded a country home for needy young men with that Catholic comrade.

To get to know agriculture, he hired out as a farmhand to a farmer in the Saale Valley. During this time, he became engaged to Margarete Schulze, an elementary school teacher, who was to accompany him for many decades as a faithful wife and mother of four children. Another time, Heinrich Ogilvie was in the village Redentin near Wismar in Mecklenburg to run – all by himself – a small, rather neglected farm. During this time, Rudolf Steiner’s book How to Know Higher Worlds came into his hands. He read it up to the middle but then put it aside with the verdict: “It is excellent, but it is not for me.”

There in Redentin, suddenly, unannounced, a strange student stood in front of him in the stable. It was the summer of 1921. Gottfried Husemann had set out on his journey after the “June Course.” Among other addresses, he also had Heinrich Ogilvie’s with him, which he had received from Arnold Goebel and Waldemar Mickisch. Gottfried Husemann, the foreign student, invited Heinrich Ogilvie to come to the “Autumn Course” in Dornach. But the latter did not want to know anything about it and sent him away. Just then, his fiancee came along and said, “Bring him back, bring him back, join them, this is your path!” But Heinrich Ogilvie did not do it.

He was asked in Marburg/Lahn to take over the leadership of a “social work-community” and establish a rural folk high school in the spirit of the ideas of Sigmund Schulze and his “Sozialen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Berlin-Ost”. Three professors, among them Paul Natorp and Rudolf Otto, acted as promoters of this enterprise.

Rudolf Otto wanted Heinrich Ogilvie to be the secretary of his “World Federation of Religions.” Ogilvie also rejected this. His ideal, which he wanted to serve, was: Everything in life should become a sacrament.

At Easter 1922, he became director of the Municipal Adult Education Center in Kassel. Quakers had provided a salary of thirty thousand marks for three months in advance. (There was inflation.) With this security, Heinrich Ogilvie thought he could marry. On April 12, 1922, his father’s seventieth birthday, the civil marriage took place. Three days later, his father died suddenly. Again, death was closely connected with a major step in his destiny. The marriage produced three sons and a daughter.

After the meeting of those who had decided to found The Christian Community in Berlin in March 1922, Richard Gitzke went to Kassel to prepare for the formation of a congregation there. He also appeared at the Volkshochschule [folk high school] of Kassel and invited Heinrich Ogilvie to attend his two lectures.

In the previous winter of 1921/22, Heinrich Ogilvie had first experienced Rudolf Steiner at his lecture given in Frankfurt. Ogilvie noticed on the train ride back at night to Marburg that in discussion with other listeners, he defended Rudolf Steiner, although the lecture had given him nothing, as he thought. Then, in Kassel, it was similar. Heinrich Ogilvie attended Richard Gitzke’s lectures and found himself in the role of the interpreter in the subsequent discussions, without having connected with anything that was said.

Heinrich Ogilvie did not want to become a member of the religious renewal movement. But there must be something to learn in the group, he thought. Therefore he wanted to get to know these people. He went to Breitbrunn. The people of the circle and most of what they said seemed strange to him. He had to endure severe trials of the soul and transformations: “A presentation by Harald Schilling on “Workers and Destiny” overturned my whole socialism.”

Toward the end of the meeting, he decided to go to Dornach to co-found The Christian Community. Now it was clear to him that “an objective religious life in cultus and sacrament creates foundations also for the solution of the social question.” He asked his wife by telegraph to come to Breitbrunn; she was to be involved in the decision. She then told him: “I told you right away that this is your path. Of course, I will go with you. But we should not have married, for you must be unmarried.”

By the end of the weeks in Breitbrunn, Heinrich Ogilvie had canceled the pastoral care of communist workers that he had already promised to some factory owners in Zeitz, Saxony. Now he was free for “the cause.” The will that had long before animated the twelve-year-old at the death of his mother was fulfilled. On September 16, he was ordained by Emil Bock and then sent out as a pastor of The Christian Community.

He wanted to found a congregation in Dortmund. A proper room could not be found – only a small chamber in Annen with a widow who had given birth to twenty-two children. Every morning he drove to Witten to work ten hours a day as a hauler. But his health could not stand this for more than half a year: “Dust lung” forced him to stop. After discussions, lectures, and courses, however, first a human basis and then also a financial basis for community work arose. It still took a whole year before the first Consecration Service could be held in Dortmund in the fall of 1923.

Despite all the difficulties that had to be overcome everywhere when the first congregations were founded at that time, five of the founders had to struggle with particular obstacles: Herman Groh, also Wolfgang Schickler in Essen, Walter Gradenwitz in Düsseldorf, Gottfried Husemann in Cologne and Heinrich Ogilvie in Dortmund.

For Heinrich Ogilvie, this first period of pioneering work lasted until the spring of 1925, when his strength was exhausted. He recuperated in the sanatorium run by anthroposophical doctors in Gnadenwald near Hall in Tyrol and then in Breitbrunn on Lake Ammersee in Upper Bavaria, where he was a guest of Margareta Morgenstern and Michael Bauer. He regained the health that allowed him to accept the request to move to the Netherlands to found The Christian Community there.

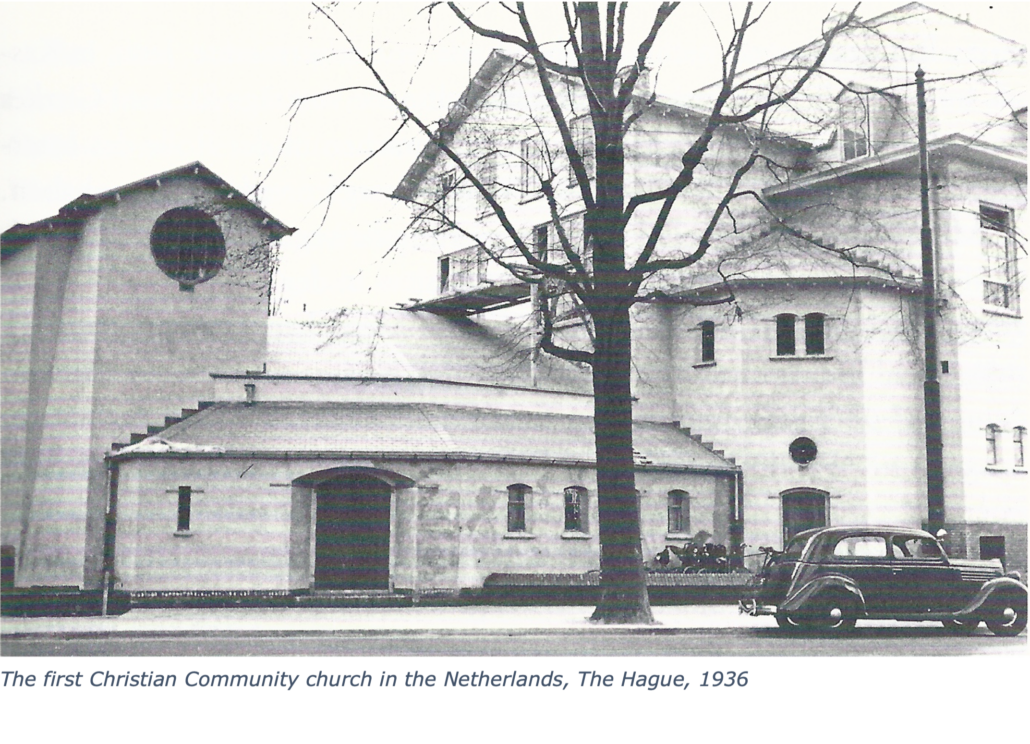

After Emil Bock’s first visit to the Netherlands in November 1924, a preparatory group for the founding of The Christian Community had formed in The Hague. The group invited him to lecture again in November 1925. On this occasion, Emil Bock baptized two children, and the Dutchmen Ludovicus Mirandolle, Gerrit Gerretsen, and Cornelis Los decided to seek the priesthood. As early as January 1926, Emil Bock again traveled to the Netherlands together with Friedrich Rittelmeyer and Heinrich Ogilvie. In addition to lectures, Rittelmeyer held the first Consecration of the Human Being in a small circle on February 7, 1926. On Palm Sunday 1926, the first Consecration Service was publicly celebrated by Emil Bock in The Hague and simultaneously by Heinrich Ogilvie in Amsterdam. The latter decided to stay in the Netherlands and took care of the translation of the text of the Consecration Service, together with the three aforementioned Dutchmen and Jeanne Brunier. As a result, on St. John’s Day 1926 in The Hague, Ogilvie celebrated the first Consecration Service in Dutch.

In the following months, he prepared the founding of congregations also in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. The founding in The Hague occurred on November 13, 1926, with 20 people. Initially, celebrations were held in a private house. The later co-workers, Ludovicus Mirandolle, Gerrit A. Gerretsen, and Cornelis Los, were actively involved in this first community established outside the German-speaking area. After Gerretsen’s and Los’s ordinations on December 19, 1926, Heinrich Ogilvie moved to Amsterdam, where community life was concentrated in the house at Johannes-Verhulststraat 41 for many years, starting in 1930.

In the 1930s, Heinrich Ogilvie filled in for Gottfried Husemann’s Lenker activities in the Ruhr region before he himself was given the Lenker’s office in 1938. In 1935, The Christian Community was officially recognized as a church in the Netherlands by the Dutch Ministry of Justice. In the same year, the congregation was able to move into the very first room it had constructed for the sacraments. When the National Socialists (Nazis) occupied the Netherlands in 1940 during the Second World War, outer conditions were oppressive but strengthening for the community: The congregation in Amsterdam also had forty Jewish members. In 1941 Heinrich Ogilvie was banned from working. However, a high police officer named Ogilvie – a sixth cousin – repeatedly allowed the personnel file to disappear at the bottom of the mountain of files.

In 1945, his community work and his Lenker activity from 1938 could be taken up again publicly. In Amsterdam, the purchase of a house was possible. In 1948 the well-known conference center “Land en Bosch” was built, where many children’s and youth camps, conferences, meetings, and synods took place over several decades. In 1956 the retirement home Valckenbosch was opened in Zeist, and in the following decade, the three impressive church buildings in Zeist, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam.

As a result of a serious accident in 1956, in which Ogilvie re-injured the leg wounded in World War I, he had to endure severe pain for eight months – deliberately without narcotics. Annual recuperative stays in Switzerland and many trips to almost all European countries and the Near East were also part of his life. Especially appreciated is his translation work. Ogilvie is to be thanked for a complete translation of the New Testament into Dutch and, in the last years of his life, into German.

With his wife, he moved to the retirement home in Valckenbosch. After her death, Heinrich Ogilvie continued to work there with unbroken alertness and his willful spontaneous temperament until he died in Zeist on February 15, 1988 – a pioneer of The Christian Community of a very original kind.

Ich hatte als junger Mensch die Gelegenheit, Heinrich Ogilvie und seinen Bruder Karl Ogilvie, ebenfalls Priester der Christengemeinschaft, zu begegnen. Beides sehr gute und starke Persönlichkeiten, mit sehr viel Ausstrahlung und feinfühligem Tiefsinn. Selten so etwas erlebt.