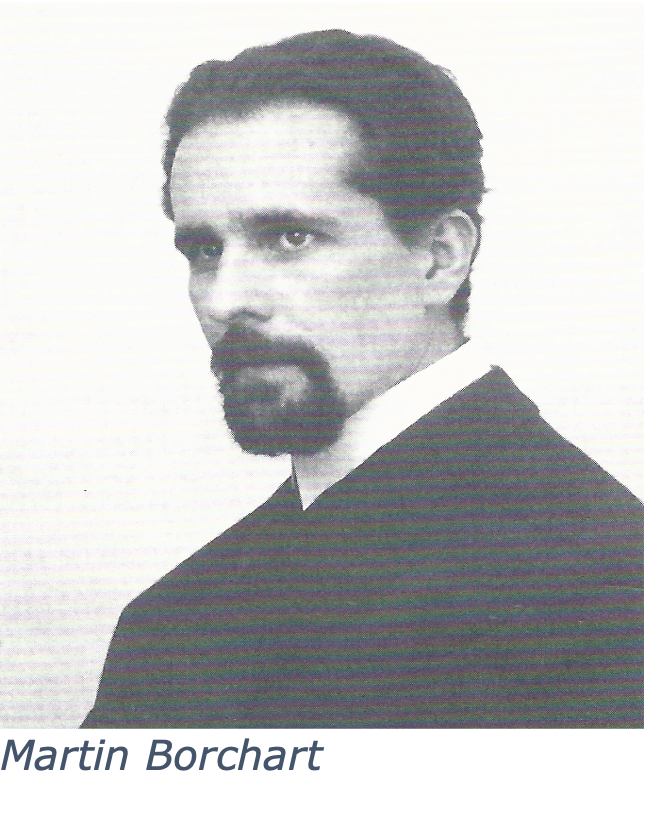

Martin Borchart

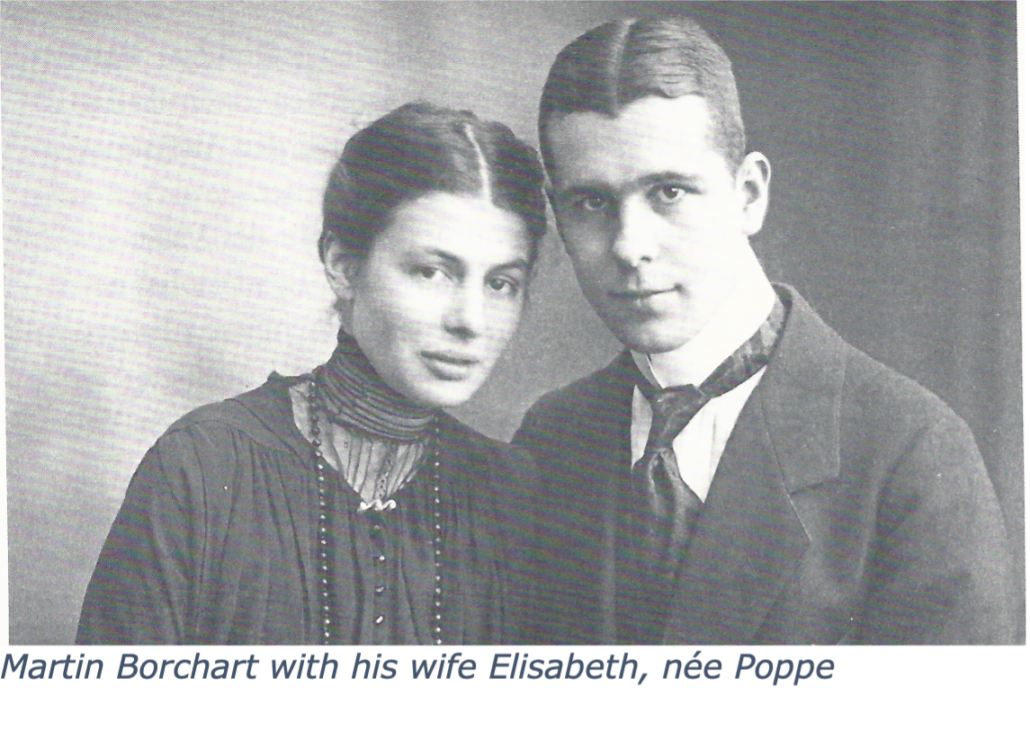

Martin Borchart

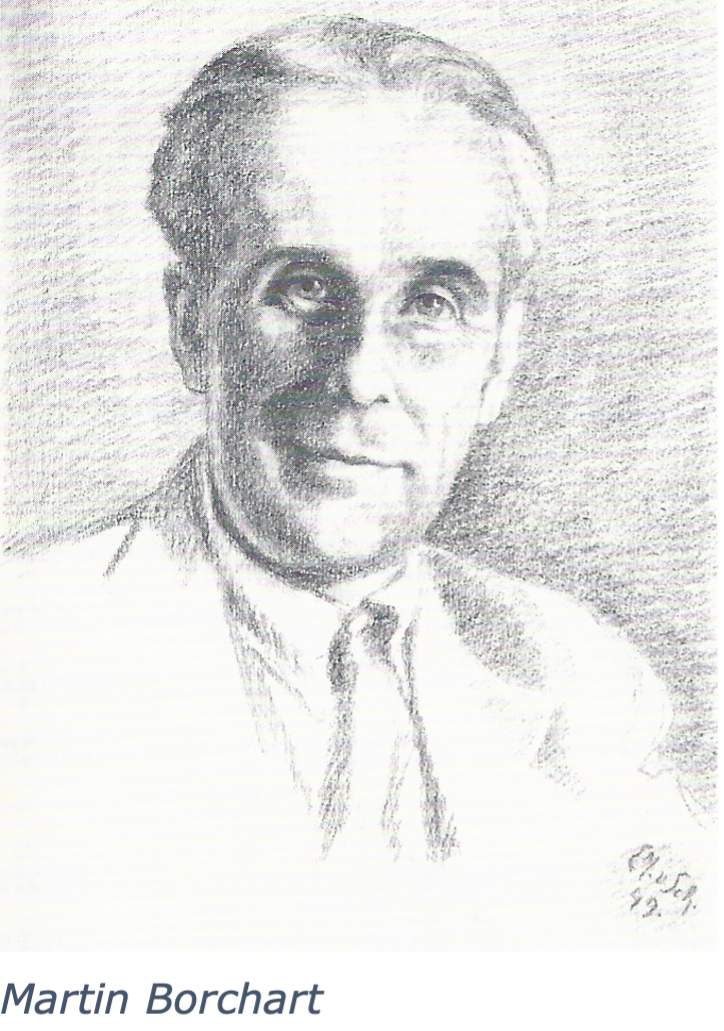

Martin Borchart

June 3, 1894, Berlin – December 19, 1971, Stuttgart

Martin Borchart, a philosophy student in Marburg, together with his wife Elisabeth, née Pappe, created the conditions for an initial inquiry to Rudolf Steiner in 1920, resulting in the founding of The Christian Community.

Martin Borchart was born in Berlin on June 3, 1894, the second son of his parents. His brother Walter was three years old at the time, and from his father’s first marriage, there was a stepsister twenty years older. His father, a principal at Berlin elementary schools, was the 39th schoolmaster of his relatives, who came from the Brandenburg area. Martin’s mother was also a teacher. She came from a Silesian estate.

Martin Borchart experienced his school days as dreary and hardly stimulating. But the buildings and schoolyards, including the school gardens, were the playground for him and his three cousins, with whom he was constantly together. His father’s school and official residence were located at Jannowitzbrücke, later at Schlesischer Bahnhof in eastern Berlin. Martin attended the Realgymnasium after elementary school. He received private lessons in Latin from a candidate of theology whom he had met in 1911 on the occasion of a summer stay on the North Sea island of Wangerooge. This was Rudolf Bultmann, the demythologizer of the Bible, who later became famous. He suggested that Martin Borchart study later in Marburg.

From his childhood, Martin Borchart reported a ‘waking dream’ in which demonic beings with frightening grimaces appeared and beset him, as he later found depicted on Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altar in Colmar in the picture of the Temptation of St. Anthony. In 1913 he passed the Abitur, which he attributed, among other things, to the fact that he had previously dreamed the subject of the German essay – “Die Weltgeschichte ist das Weltgericht” (“World History is the World Judgment”).

Although a third kind of dream was later to play an important role in his life, Martin Borchart was not a dreamer; rather, throughout his life, he maintained a particularly spiritual openness, with all alertness. His gentle humor and his fine smile were visible signs of this.

After graduating from high school, one year before the beginning of World War I, he studied theology for two semesters in Berlin. He caught up on the humanistic baccalaureate (with Greek and Hebrew). He then summed up his experience of these studies in the devastating verdict: when you become a pastor, “you take with you into practical work what you have already brought to the university in terms of religiousness, minus what you have been deprived of by studying theology.”

Right at the beginning of the First World War, he volunteered for the military, for the 4th Guards Regiment. Very soon, he suffered at the front — where he had once, as it was later discovered, been very close to Emil Bock — a first wound at Langemarck. Both legs were shot through.

Later, in Russia, he was shot through the thigh. Because of, but also despite, such weakened legs, he reported for pilot training in 1916 and was accepted. In Gotha and then in Böblingen near Stuttgart, he learned to fly the small, still rather primitive, open fighter planes, whose machine guns had to be set so that they shot precisely between the rotating propeller blades, which was not always the case.

How delightfully Martin Borchart could tell about the training flight whose goal he had determined as the place of residence of the lady who was  one day to become his wife. On the flight from Böblingen to Heidenheim, he did not find the previously determined topographic landmarks in the actual landscape below. He had ‘flown astray’ and now tried to read the place name in a low-level flight over a train station; instead, he read Platform 1 and, on the next approach, Platform 2. After landing among fruit trees, he received information from a farmer that this was Goeppingen. The flight was continued, ending in Heidenheim, but because of adverse wind conditions, he landed on a field in whose immediate vicinity much later The Christian Community’s church was to be built. The couple in the house near the emergency landing site told him that Miss Poppe had unfortunately just left. They asked whether he knew, by the way, that she was an anthroposophist. While the housewife was already on the next topic — the abominable new invention of chewing gum in America, with which one could pull long strings out of the mouth— the master of the house enlightened the guest who had landed so rudely from the sky, “… the anthroposophists believe in the astral body”. The merchant and world traveler Alfred Meebold had written a book about it, The Path to the Spirit.

one day to become his wife. On the flight from Böblingen to Heidenheim, he did not find the previously determined topographic landmarks in the actual landscape below. He had ‘flown astray’ and now tried to read the place name in a low-level flight over a train station; instead, he read Platform 1 and, on the next approach, Platform 2. After landing among fruit trees, he received information from a farmer that this was Goeppingen. The flight was continued, ending in Heidenheim, but because of adverse wind conditions, he landed on a field in whose immediate vicinity much later The Christian Community’s church was to be built. The couple in the house near the emergency landing site told him that Miss Poppe had unfortunately just left. They asked whether he knew, by the way, that she was an anthroposophist. While the housewife was already on the next topic — the abominable new invention of chewing gum in America, with which one could pull long strings out of the mouth— the master of the house enlightened the guest who had landed so rudely from the sky, “… the anthroposophists believe in the astral body”. The merchant and world traveler Alfred Meebold had written a book about it, The Path to the Spirit.

From his experiences in the war as a reconnaissance pilot (from Metz), there is nothing to report further here. In January 1918, the engagement was celebrated; then, on June 18, his wedding with Elisabeth Poppe. Three children were born to the couple. Through his wife, he found access to anthroposophy. She had already, at the age of twenty-one, been accepted as a member of the Theosophical Society by Rudolf Steiner in 1912. After Martin and Elisabeth Borchart had rented a six-room apartment in Marburg/Lahn in the old town (at Marktgasse 18), lively work with like-minded people could be established in its rooms. First, they founded a local group of the League for Threefolding together with the German-American Friedrich Oehlschlegel, who was soon appointed as one of their first teachers at the newly founded Stuttgart Waldorf School. When seven people were together, they founded a branch of the Anthroposophical Society. Martin Borchart became the branch leader.

A Düsseldorf lawyer’s son and student of painting, later of theology, from Munich contacted him. It was Johannes Werner Klein with whom the following events were to take place. Both students had switched to philosophy out of disappointment in their theology studies. Together they eagerly studied Rudolf Steiner’s lectures. On Friday, January 30, 1920, in the middle of the semester, Elisabeth Borchart woke up her husband in the morning: They had to go to Dornach on Monday to visit the first Goetheanum because there could be a train accident. Since her husband hesitated, she said that he could ask Mr. Klein if he wanted to go with them. This request was made in front of the College, and afterward, Johannes Werner Klein agreed to go along; the next day Margarete Deussen joined him.

The trip was delayed. Because of incipient inflation, money had to be obtained. They took along some items for sale in Switzerland. Equipped with a membership card of the “Johannes [Goetheanum] Bau-Verein” and some issues of the house magazine of the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory in Stuttgart, the four travelers identified themselves at the consulate in Frankfurt, saying that they were welcome as students in Dornach.

A week after the idea of going to Dornach to visit the Goetheanum emerged, the four travelers had reached their destination and found that a lecture by Rudolf Steiner had been announced for the evening. (Today, this lecture of February 6, 1920, can be read in GA 196). Rudolf Steiner spoke several times about the necessity of the renewal of Christianity; that one must learn to think and act humanely, not bound to nation or tribe, as before. And then: “These things can inspire you to the question: But then what should the individual do?”

Now, in retrospect, it may seem as if those words had been spoken specifically for the new young guests from post-war Germany. In any case, Johannes Werner Klein felt inspired to ask Rudolf Steiner for an appointment, which took place on Sunday, February 8 [compare the chapter on J. W. Klein]. Rudolf Steiner noticed during this conversation that Johannes Werner Klein had not quite understood him and therefore asked for his companion, Martin Borchart; if he had a question, he would be available for him. Martin Borchart knew nothing of the content of the conversation that had just taken place between Rudolf Steiner and Johannes Werner Klein and had no question of his own. Borchart had already discussed his doctoral thesis with Rudolf Steiner and had also received a topic for it, which unfortunately has not been passed down; it did not materialize later because of the founding of The Christian Community.

However, the question about the third church, about Johannine Christianity and its religious form, was raised by Johannes Werner Klein (following the thoughts of the philosopher F.W. Schelling in his Philosophy of Revelation). This was followed up on later. Almost a year and a half had to pass before, again with Martin Borchart’s help, the correctly formulated request of a group to Rudolf Steiner made possible the promise of a first course oriented toward religious renewal. At that time, on May 22, 1921, when they were struggling for the right formulation of this request, Martin Borchart had just the day before acquired a newly published lecture cycle by Rudolf Steiner. During the night, he immediately studied the first three lectures (“Cosmic and Human Metamorphosis,” today in the Complete Edition Nr. 175: Building Stones to a Knowledge of the Mystery of Golgotha). More than four years earlier, on February 20, 1917, Rudolf Steiner had stated in Berlin, in the presence of Friedrich Rittelmeyer, the necessary distinction between spirit-cognition (anthroposophy) and religious practice. Spirit-consciousness is kindled through religious practice, and spirit-knowledge is acquired through anthroposophy. Martin Borchart spontaneously grasped this distinction at that time. He conveyed this quotation to Gottfried Husemann, who then succeeded in formulating the question about new forms of Christian religious practice. Thus, also through Martin Borchart’s contribution, the “June Course” for the preparatory group of eighteen students in Stuttgart became possible. From then on, he was a witness at all stages of the founding of The Christian Community.

On September 16, 1922, at the age of twenty-eight, he was ordained to the priesthood by Emil Bock. He actually wanted to go to Bremen, where he had hoped for help from an uncle to found a congregation there. However, he left this city to his friend Johannes Werner Klein and became the founder of the congregation in Dresden (1922), then in Bayreuth (1924), before becoming pastor in the Stuttgart congregation in 1925, where he found the center for all his further activities.

On September 16, 1922, at the age of twenty-eight, he was ordained to the priesthood by Emil Bock. He actually wanted to go to Bremen, where he had hoped for help from an uncle to found a congregation there. However, he left this city to his friend Johannes Werner Klein and became the founder of the congregation in Dresden (1922), then in Bayreuth (1924), before becoming pastor in the Stuttgart congregation in 1925, where he found the center for all his further activities.

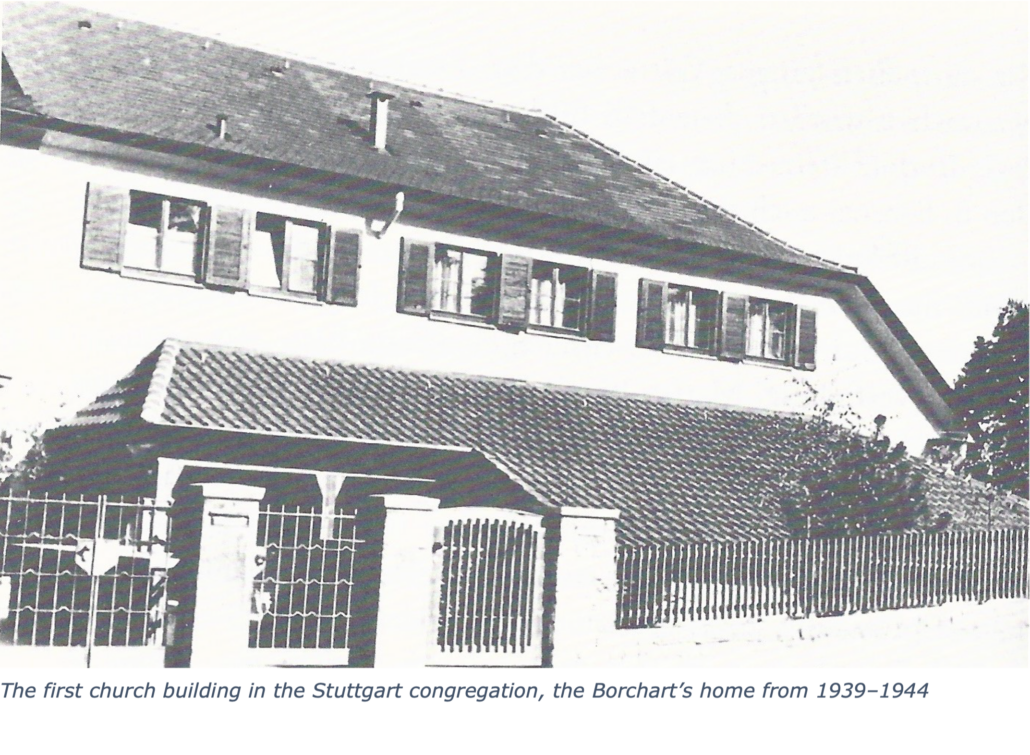

From then on, Martin Borchart worked as a priest in the Stuttgart congregation with Kurt von Wistinghausen, Erwin Schühle, Arnold Goebel, Friedrich Rittelmeyer, Emil Bock, Hermann Beckh, and many other colleagues who were only active there for a short time. In 1933 he was able to live with his family in the newly built seminary house. In 1940, however, human relations with Mr. and Mrs. Husemann, who lived in the seminary, made it seem more favorable for him and his family to move into the parish house in the Werfmershalde, into the apartment above the consecration room. From 1937 on, he suffered from the consequences of a motorcycle accident.

In 1938, after Friedrich Rittelmeyer’s death, Martin Borchart was appointed Lenker for Stuttgart and the Württemberg Swabian communities. This was followed by the banning of The Christian Community by the National Socialists on June 9, 1941, and several weeks of imprisonment in the Welzheim concentration camp. During the prohibition period, he prepared for an interpreter’s examination in English and Russian in Heidelberg but, for unknown reasons, did not take the final examination. Instead, in October 1942, he joined the Stuttgart office of the Central Dairy Kuhn, Rottenburg/Neckar, as office manager, personnel supervisor, and public relations officer. During the fire in the community center in 1944, he contracted severe smoke poisoning; from then on he suffered from respiratory problems.

In 1938, after Friedrich Rittelmeyer’s death, Martin Borchart was appointed Lenker for Stuttgart and the Württemberg Swabian communities. This was followed by the banning of The Christian Community by the National Socialists on June 9, 1941, and several weeks of imprisonment in the Welzheim concentration camp. During the prohibition period, he prepared for an interpreter’s examination in English and Russian in Heidelberg but, for unknown reasons, did not take the final examination. Instead, in October 1942, he joined the Stuttgart office of the Central Dairy Kuhn, Rottenburg/Neckar, as office manager, personnel supervisor, and public relations officer. During the fire in the community center in 1944, he contracted severe smoke poisoning; from then on he suffered from respiratory problems.

In former times, he had been called ‘the handsome Martin.’ The tall, slender figure, leaning a little on his cane with the silver knob, a fine smile on his face: this is how the Stuttgart community experienced him as their priest for many decades.

A special concern of his was the annual conference of the Swabian communities. The people should get together from many places and experience The Christian Community. On the occasion of such a conference in 1965, the Swabian Building Fund was founded, a free economic association of the congregations for the financing of church buildings. Thus, for example, the congregations in Esslingen, Ulm, Murrhardt, Tübingen, Stuttgart, and Überlingen were able to build their churches. Thanks to this joint institution, many church centers have been built to this day.

Within the circle of priests of his lenkership and under his free and benevolent gaze, a fraternal common ground around the need for Honorarium requirements was able to unfold in the form of the first salary network in The Christian Community. From this side, the germs of new social forms were sown.

For decades Martin Borchart had to bear the brunt of the character of his founding colleague Gottfried Husemann, who died remarkably close to him. Martin was almost always silent, rarely and only quietly voicing his opinion. He lives in memory with the smile of a mildness that only borne pain makes possible; he could rejoice royally over what his pastor colleagues achieved, especially the younger ones.

Thus, in the last years of his life, he could often be heard saying gratefully and joyfully: “Lord, now you let your servant go in peace.” He died on the fourth Sunday of Advent, December 19, 1971, in Stuttgart, a few months after the death of his son Heinz, who had also become a priest. His crossing of the threshold led him directly into the days of the Christmas events. The Christian Community owes to his selflessness the decisive act of mediation in the hour of its foundation.

MEMORANDUM

The realization that a renewal of religious life was necessary for the salutary progress of humankind, and the will to help in this, brought together the participants of the Stuttgart Theology Course in June 1921. These young theologians were of the opinion that the theological faculty could not give them a fruitful preparation for their goal, and a state-church office could not give them the right field for their work. Therefore they turned to Dr. Steiner to receive from him what anthroposophy could give them to prepare them to found viable Christian communities. Practically, the work of financing was immediately set in motion at that time, which was to create a basis for making the spiritual work possible. Since a certain financial basis now seems to have been created which could support our work in the beginning, and since many signs in the present seem to me to indicate that we would be fulfilling a time requirement if our work were to begin now, and that perhaps the appropriate period could be missed by prolonged hesitation, it seems to me necessary that those should come together who are willing to put their full strength into it at once. An educational course led by Dr. Steiner, seems to me to be an indispensable prerequisite. I can overcome the consciousness of my inadequacy and unworthiness only by hoping to grow through the great cause. And so I now want to stand up for it completely, giving up my previous work.

-Martin Borchart

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!