Songs for all Seasons

We are pleased to announce a new offering:

Songs for all Seasons

a musical collection of 55 songs for

The Consecration of the Human Being

Thirst

If there is anything that binds us to the earth, it has to be the thirst for existence. It shows itself in countless forms, not only in hunger and thirst for food and drink. Whenever we walk through the streets of a city we will quickly recognize how the thirst for existence dominates our lives.

Although Christ’s realm is not of this world, during His life on earth He knew hunger and thirst, longing and temptation, hardship and pain. He is the only one of all the inhabitants of heaven who knows earthly existence and all the temptations it brings, out of His own experience. “Give me to drink.” (Jn 4:7) It sounds not only in the heat of the day, but to the bitter end: “I thirst.” (Jn 19:28) The angels know nothing about this. Even the Father doesn’t. None of them ever became a human being of flesh and blood.

The Risen Christ no longer knows hunger and thirst for earthly substances—but it is His thirst for our existence that makes Him long to be with us, all days, to the fulfillment of the world. His meal is not only the most precious gift on earth, it is also the most precious gift we can give Him. “I thirst. I only have what people give me. I take nothing.” Thus someone heard Him speak in His longing to share the meal with us.[*]

What a surprising expression: He wants to share with us the meal He bestows on us. In this game of giving, taking, and sharing the enigmatic word becomes real, which He spoke as a promise for the future: “The water that I shall give him will become in him a spring of water welling up to eternal life.” (Jn 4:14)

Only if I give myself to Him as He has given Himself to me, the meal is fulfilled and his thirst for our existence is quenched.

-Rev. Bastiann Baan, June 11, 2023

[*] Gabrielle Bossis.

Pentecost

Everywhere in nature presence of Spirit reveals itself. Wherever you look, everything is ordered and arranged according to wise laws of nature, in which every plant, every animal forms an indispensable link in the whole. We are hardly able to unravel some of this perfect order in the science we call ecology, a word the literal meaning of which is: logic of the household of nature. Nothing in this order seems to be left to chance.

Our human order is child’s play compared with the perfect laws of nature. In our lives “ecology” is often hard to find. True, in our origin we were made in God’s image, but this primal image is disformed and mutilated again and again into God’s counter image, the unholy spirit.

At Pentecost, Christ wants to send the Spirit into our souls—provided we make room for the Spirit. His presence of Spirit needs our presence of spirit. And if there is no space for Christ in us, the breath of the Spirit blows to other places on earth. The Spirit blows not only where it wills, but also to the dwelling places we prepare for it.

For this reason the Holy Spirit is also called the Paraclete—this means literally “the called one.” May our prayer, the great prayer of the Consecration of the Human Being, become a flaming call for the Spirit, so that He can find a lasting home in our community!

Rev. Bastiaan Baan, May 28, 2023

Kurt Philippi

Die Gruender der Christengemeinschaft: Ein Schicksalsnetz

By Rudolf F. Gaedeke

Translated by Cindy Hindes

October 16, 1892, Munich – March 19, 1955, Nuremberg

Kurt Philippi was born in Munich on October 16, 1892. His father had a store for shoemaking supplies; his mother was a court actress, first in Darmstadt, then in Munich. In the year after his birth, the young family moved to Teplitz in Bohemia, where his father took over the management of a shoe factory. There, in Teplitz, his siblings Else and Paul were also born. Else died of diphtheria at the age of four.

Kurt Philippi’s early childhood ended in 1899. The family moved to Berlin, where his father became a salesman after losing almost his entire fortune as co-owner of the Teplitz factory.

The boy began his schooling there in Berlin. His last school was the Hohenzollern-Reformgymnasium Schöneberg, which he left in February 1912 with the certificate to study German and new languages. This decision was based on his talent for these subjects and his desire to become a librarian. However, after leaving school, various fateful encounters and experiences led him to study Protestant theology at the University of Berlin in April 1912.

In October 1913, his father died of a stroke. Through iron diligence, supported by Kurt’s mother, who managed the business correspondence, he had created a financial basis again and thus made Kurt’s studies possible.

In February 1915, Kurt Philippi was called up for military service in World War I. He first took part in the Russian campaign and then went to the Western Front in France. He experienced all the phases of positional warfare with their immense human losses in battle until the retreat.

At the beginning of October 1918, Kurt Philippi fell ill with severe influenza on the Western Front and had to be sent to the reserve military hospital in Aschaffenburg. The disease had not yet been overcome when he was released in November. This not fully healed illness continued to make his physical constitution appear fragile. It was certainly a major cause of his many years of suffering and his relatively early death.

He resumed his theological studies in Berlin in the winter semester of 1918/19 and passed his exams in the spring of 1922. However, great doubts of faith had arisen in Kurt Philippi, probably not least due to his war experiences. They made it seem impossible for him to enter a parish office of the regional church. The Protestant doctrine of the sacrament and the administration of the sacrament, in particular, made it impossible for him to cooperate. Therefore, during his last semesters of theology studies, he had already taken up training in the institute of Dr. E. Drach, lecturer for language education and the art of lecturing at the University of Berlin. He completed this one-and-a-half-year course of study with a diploma as a ‘teacher for voice training and performance art, especially for purposes of the German school’.

In his second period of study after the World War, Kurt Philippi became acquainted with Friedrich Rittelmeyer, Emil Bock and the circle that had formed around them and thereby with anthroposophy. Unfortunately, we do not know how these encounters took place. Kurt Philippi only related that he joined everything “with enthusiasm”.

His enthusiasm became even stronger in the preparation for religious renewal. Here it was a matter of a new understanding of the sacraments comprehensible to present-day consciousness and the intention to cultivate a completely renewed form of cultus.

Thus Kurt Philippi became a co-founder of The Christian Community. He reported how much he was touched by Michael Bauer’s visit to Breitbrunn during the preparatory meeting for Dornach. Bauer impressively spoke to the circle that the most important thing for a spiritual aspirant, i.e., a pastor, is “inner composure,” which is true “wood-chopping work,” and yet must proceed without any physical tension.

Emil Bock ordained Kurt Philippi on September 16, 1922, shortly before Kurt’s 30th birthday, as the eighteenth of the whole circle.

He went from Dornach to Magdeburg, where he had already prepared a church foundation. This city of Ottonian Christianity on the Elbe, directed by the Kaiser, did not immediately open up to the newcomer. It was a difficult time. Kurt Philippi soon went to Naumburg-an-der-Saale, where he replaced his Berlin friend Dr. Eberhard Kurras. His time in Naumburg also lasted only briefly – as did his following time in Leipzig. In February 1926, after three-and-a-third years of teaching in three different places, Kurt Philippi came to Nuremberg, the site of the imperial castle.

In Nuremberg, he accomplished his real life’s work; he worked there as a quiet, always active congregational pastor and companion of his fellow pastors Wilhelm Kelber, Karl Ludwig and later Eberhard Kurras. From his marriage in Nuremberg came two sons. He was there when The Christian Community was banned on June 9, 1941, and remained there with his family during the war. He was spared military service for health reasons until the final phase, when he finally had to enlist in the Volkssturm. From 1941 to 1943, he trained as a bookseller at the M. Edelmann company in Nuremberg.

During the four years of the ban, he was the only pastor present in Nuremberg and thus could maintain personal relationships with the parishioners in the hard-hit city. During the war, he accompanied in prayer his friends in the field, especially those who had fallen.

Immediately after the end of the Second World War and the collapse of the Third Reich, he began the work in the community when his colleagues could not yet be back in Nuremberg. At Pentecost 1945, the first Consecration Service after the war was read with congregation members and celebrated soon after.

Immediately after the end of the Second World War and the collapse of the Third Reich, he began the work in the community when his colleagues could not yet be back in Nuremberg. At Pentecost 1945, the first Consecration Service after the war was read with congregation members and celebrated soon after.

He prepared confirmands for twenty years, and time and again, he brought a circle of players to impressive performances in the Oberufer Christmas plays.

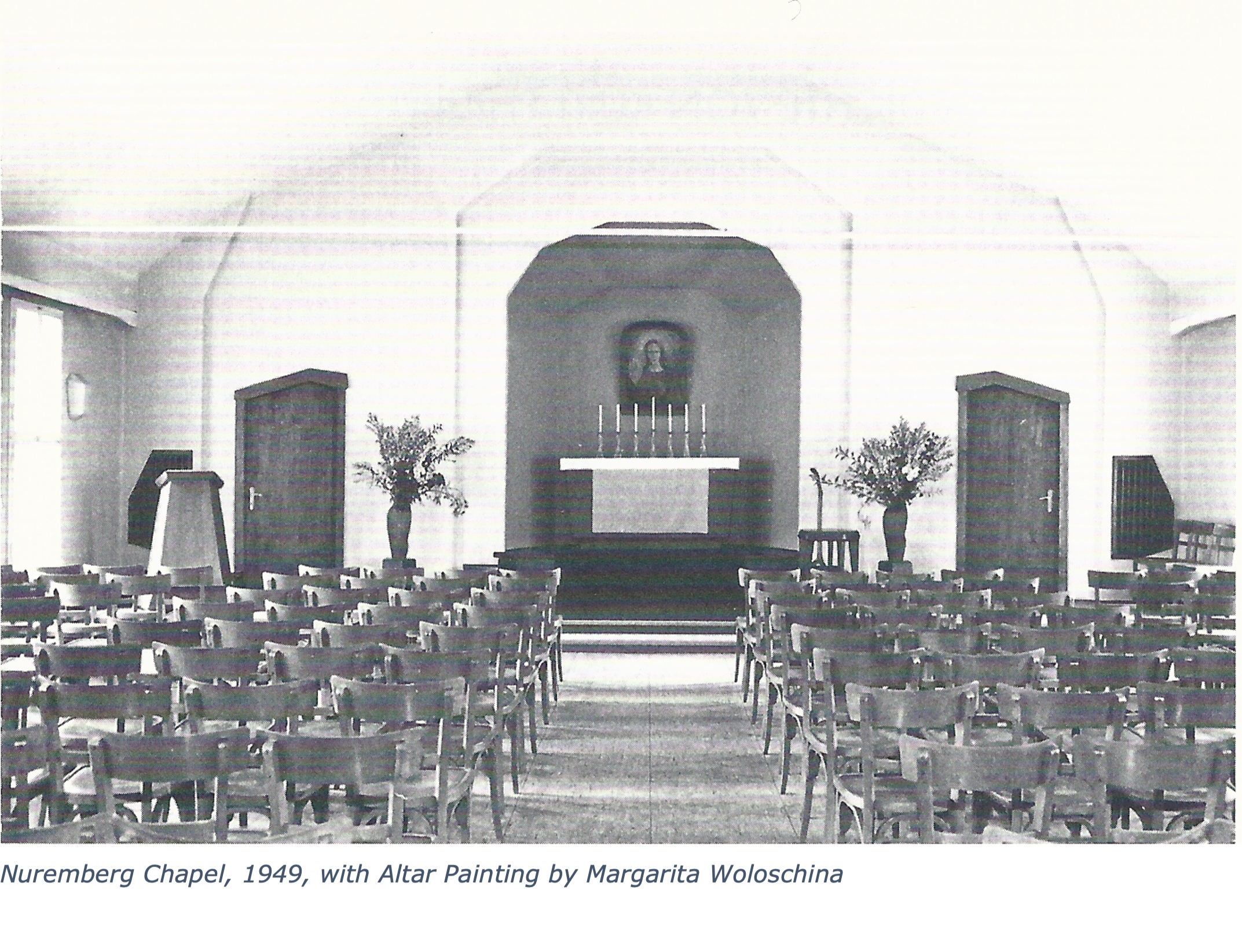

Kurt Philippi also cultivated contacts with the authorities and thus made it possible to build a community center as early as 1948/49, just outside the old city wall under the Kaiserburg on a partial plot of the Schwanhäußergarten. His quiet manner inspired confidence, and the building was able to come about despite all the adverse circumstances. It was not until 1976 that it had to make way for a much larger church building.

Emil Bock consecrated this first building on December 18, 1949. One year later, Kurt Philippi experienced the same symptoms of illness as in 1918. Recuperation and sanatorium stays were necessary. But the disease (Parkinson’s) could not be stopped. Much patience had to be exercised. A large circle of friends accompanied his time of suffering.

He suffered in full consciousness until shortly before his death on March 19, 1955. He passed away in the sixty-third year of his life, like so many of the founding circle.

Kurt Philippi’s quiet, restrained nature was never forward. Everything that stood out, everything conspicuous, was alien to his nature. In silence, he expressed many things that moved him in the form of poems — without wanting to be a poet. He wrote many such poems, often on current events. His life would be incompletely represented if some of these poems were not considered. The poems “Den Kindern unserer Zeit [The Children of our Time]” he sent to Emil Bock shortly before his death; the second and third probably speak more of his own longing.

MEMORANDUM

Inspired by Mr. Klein’s remarks, the following has become clear to me on repeated reflection: If the goal of religious renewal set forth in the Dornach Commitments is to be realized in the foreseeable future, it is necessary that those who wish to work for this goal join together in a community during the Berlin University Week to prepare themselves for their public work as soon as possible in close cooperation under the direction of Dr. Steiner, above all to strengthen the power and purity of the religious impulse within themselves and to acquire pedagogical insights and skills. If possible, public lectures should begin this summer. As desirable as greater inner maturity and, ultimately, the attainment of academic degrees and certificates of competency would be for us, it seems to me at the present time to be incomparably more important that our seeds be sown while the wind is still reasonably calm. So I would urge Dr. Steiner to be helpful to us in our preparation for public activity. I am determined, after such preparation, to devote myself immediately to public activity in the interests of our cause if the Central Office deems the time suitable and me qualified to do so.

Kurt Philippi, Berlin-Friedenau, November 26, 1922

The Ruler of This World

Wherever and whenever you look around you, the ruler of this world is always present—so prominent, so overpowering that the hidden power of the good is mostly really hard to find. It sounds so simple in the last words of Christ, and it is so difficult to recognize in our daily existence: “…the decision has already been made about the ruler of this world.” (Jn. 16:11) It often looks as if the ruler of this world has free play.

Only when you try to imagine what Christ did when He stood face to face with the adversary power can you begin to understand these enigmatic words. How did He look? What did He see? He saw a deformed being, a demon, estranged from his origin and purpose. Christ Himself, through whom “all things came into being” (Jn.1:3), recognized His creature. And the demon recognized his origin and purpose—and surrendered.

We human beings are still far from able to vanquish the ruler of this world on our own power. But together with Christ we can subdue him. One of the psalms says it with the words:

With the Lord on my side I do not fear

What can man do to me?

The Lord is on my side to help me;

I shall look in triumph on those who hate me. (Ps. 118: 6-7)

Watch the adversary power, together with Christ. Look at the world through the eyes of Christ—and the ruler of this world will recognize his Lord and Master.

-Rev. Bastiaan Baan, May 7, 2023

Pay Heed To How You Listen (Lk. 8:18)

In a world where everything tries to make us seeing-blind and hearing-deaf it is necessary to look and listen with open eyes and ears. And these days that is not so simple. Cunning techniques make it possible to twist visible reality into lies. But with the spoken word this is more difficult. The human voice cannot conceal itself. To hear what is really meant you have to learn to listen right through the words.

“Pay heed to how you listen.” (Lk. 8:18) This instruction from Christ is a key to the reality behind the words. Whenever a person speaks something always sounds through it. (The Latin word persona (per-sona) literally means sound through.) What or who is sounding through when we speak? A blind person, who had developed the art of listening to great perfection, called this the moral music of the voice. The art of listening gives us the capacity to distinguish the voice of a stranger from the voice of Christ.

The Consecration of the Human Being is pre-eminently the place where we can develop this ability. Someone who had attended the altar service for many years said once: “Through the Consecration of the Human Being I have learned to lead a listening life.”

“Pay heed to how you listen.”

And if we not only listen to others, but can also inwardly listen, we will begin to recognize His voice also in ourselves. That is the Christ voice of conscience which wants to lead us like a shepherd through all the trials of life.

-Rev. Bastiaan Baan, April 23, 2023

“Peace be with you! (John 20:19-20)

“Peace be with you!’

And while He said this, He showed them His hands and His side.” (John 20:19-20)

Christ is the God with the wounds.

If there is anything that distinguishes Him from all beings in heaven and on earth it has to be the wounds in a perfect resurrection body. Wounds are plentiful among people on earth—but no human being on earth is yet risen. Countless deceased rose after Easter—but no deceased has wounds like His.

To demonstrate to his unbelieving followers that this is His identifying mark, Christ shows them His hands and His side. If that does not suffice, they may touch His wounds.

Hundreds of years later St. Francis sees in a vision an overwhelming light figure that tells him he is Christ. St. Francis looks right through the impressive figure and says: “My Lord is lowly in appearance. Show me your wounds.” Thereupon the devil flees, who for the occasion had shown himself like a wolf in sheep’s clothes.”

Christ is the God with the wounds. When He shows His wounds the words always sound: “Peace be with you.” When we hear these words at the altar He wants to let His breath stream into us to recreate us in His image and likeness. His peace is not of this world. He has wrested Himself free of pain, of death, and of demons. This most precious gift of life out of death He wants to share with us, so that we bear His peace in us—even in a world of pain, death, and demons.

Rev. Bastiaan Baan, April 16, 2023

Otto Becher

Die Gruender der Christengemeinschaft: Ein Schicksalsnetz

By Rudolf F. Gaedeke

Translated by Cindy Hindes

OTTO BECHER

January 26, 1891, Holzminden/Weser – July 19, 1954, Pforzheim

When Otto Becher died after a severe operation in Pforzheim on July 19, 1954, another of the founders of our earthly work was lost. He was sixty-three. What he had given shone as a special color in the picture of the first decades.

When Otto Becher died after a severe operation in Pforzheim on July 19, 1954, another of the founders of our earthly work was lost. He was sixty-three. What he had given shone as a special color in the picture of the first decades.

Otto Becher was born in Holzminden/Weser on January 26, 1891. He grew up in this landscape of old Carolingian spirituality near the Corvey monastery. His mother, Anna, died early. His father Emil was pious, with a personality of positive faith. His son admired him very much, even though later in his studies, Otto Becher belonged to the most radical wing of critical theology.

Something particularly straightforward lived in Otto Becher, in his whole being, but especially in his thinking and judging. “In the service of that which was recognized as true and that which was felt to be sacred, he consumed himself completely with those powers which were at his disposal.” — that was how his friend Rudolf Meyer described it.

Initially, Otto Becher had worked in Leipzig with Wilhelm Wundt in the Psychological Seminar. Then he moved to Göttingen to study the strictly phenomenological direction of Edmund Husserl. Studies in the philosophy of religion and the pedagogical seminar with Professor Arthur Titius revealed Becher’s talents so strongly that Titius invited him to teach with him. But the twenty-four-year-old refused. His honesty in discernment forbade him to pass along what was traditional and dogmatically obscure. But he studied intensively; he received a scholarship and was allowed to live in the Theologischen Stift. His external needs were always modest. When Rudolf Meyer met him in 1915, he was like a monk in his cell—but embracing all cultures in spirit.

During their heated discussions and conversations ‘in his cell’ about Julian the Apostate, the phrase emerged: “What you are looking for could be called, in the sense of Goethe, the cross entwined with roses.”

This appealed to Otto Becher in the depths of his soul, after which the friends sought Goethe’s poem “The Mysteries”; it described how Brother Mark finds the gate of the Brotherhood of the Rosicrucian.

Rudolf Meyer had found his way to anthroposophy in 1916. He had heard that at the first Goetheanum building, a stage curtain was planned to show an image of the motif of Brother Mark finding the Rosicrucian Gate. Otto Becher was horrified that his friend was getting involved in such fantastic things as anthroposophy. Nevertheless, he began to familiarize himself with the new spiritual science and subsequently became a thorough connoisseur and exponent of anthroposophy.

It was clear to Otto Becher that he could not take on any position as pastor or lecturer. So he first worked as a house teacher at the Silesian castle of Lubowitz near Ratibor, from which Josef von Eichendorff came, then with Stegemanns at Gut Marienstein, north of Göttingen. He also worked for a time as an educator with Paul Geheeb at the ‘Odenwaldschule’.

When the very first circle of eighteen students gathered with Rudolf Steiner for the June Course in Stuttgart in 1921, Otto Becher was among them. For him, the consequence was to withdraw from his spiritual-scientific studies and turn to the work of religious renewal. Four months later, he attended the Autumn Course for theologians in Dornach and expressed his will to cooperate, even though he thought he had only weak forces. From May 1922, he prepared the foundation of a congregation in Breslau.

In the Breitbrunn photo, we see him standing in the middle next to Pastor Karl Ludwig. Compared to the youth of most of the participants, both were already more mature professional men. Emil Bock ordained Otto Becher in Dornach on September 16, 1922, the day of The Christian Community’s founding.

After the Dornach events, Otto Becher founded the congregation in Hannover together with Claus von der Decken. But he remained there only a year and then, at Rudolf Meyer’s request, worked in the Görlitz congregation.

This circumstance made it possible for him to attend the conference at Koberwitz Castle near Breslau from June 7-16, 1924, where Rudolf Steiner held the agricultural course that spiritually founded the biodynamic way of farming. A small insignificant episode has come down to us from those days, but it characterizes Otto Becher’s poverty and frugality. On the daily train ride from Breslau to Koberwitz, a lady noticed that Otto Becher was wearing no socks and completely worn shoes despite the wet and cold weather. She immediately made sure that he received what he needed as a gift.

In October 1924, Otto Becher, at the age of thirty-three, took up his work in the Pforzheim community. It had been founded by Walter Gradenwitz, who then worked with him for some time.

For over thirty years, he built up and maintained the congregation in Pforzheim. Of benefit was his comprehensive education in many areas, his pedagogical experience in religious education for children and youth work, but above all, his spiritually clear and modest, engaging, friendly manner.

Although Rudolf Meyer had repeatedly asked him to write, he did not publish any of his work. A wealth of manuscripts were confiscated by the Gestapo when The Christian Community was banned, and he was taken into custody for three weeks. During the time when the Christian Community was banned, he worked as a secretary in Herbert Witzenmann’s metal tube factory.

Apart from Pforzheim, he gave lectures in only a few towns in Baden. According to the judgment of his colleagues, these were true gifts of the spirit.

With his commitment as a member of the board of the school association, he promoted the founding of the Pforzheim Waldorf School. He was wholeheartedly involved in the work of the branch of the Anthroposophical Society. In addition, he was a well-known personality in that town, which on February 23, 1945, had been so severely hit by the war.

So it was natural that at Becher’s death, the mayor wrote a heartily cordial letter and that the newspaper paid detailed tribute to his work in the city.

Perhaps two things characterize Otto Becher best: The topic of his last series of lectures in the congregation was: “The Work of Christ in the Intellectual History of the Occident.” His innermost concern was to trace Christ’s activity discerningly and serve Him in worship. And secondly, he was like a secret knight who sensed his proper hour approaching. Thinking of repeated earth lives, he himself considered his rich working life only as a preparatory incarnation.

He cared for the renewed sacraments as a priest for thirty-three years.

226 Otto Becher

MEMORANDUM

For a long time I had the feeling that the will for a religious renewal, which had begun to flow at our first course in Stuttgart in June, had since then increasingly moved from the practical-religious to the theoretical-theological and thus threatened to peter out. Through Mr. Rudolf Meyer and Mr. Borchart, I have now been informed that many of us course participants have become aware of this and have decided to call for the purification of the original impulse through explanations.

I hereby join these rallies. Even if, on the one hand, the whole magnitude and gravity of our task cannot be brought seriously enough into consciousness, and the inadequacy of one’s own powers, measured against the task, is experienced in a particularly deep and painful way, I nevertheless believe that it is precisely the cliff of hidden egoism that is avoided if, trusting in the soul-strengthening and enriching effect of the spiritual knowledge that Dr. Steiner has made accessible to us, one courageously begins with practical religious work. Personal imperfections are certainly best overcome in spiritual-religious action and life itself. It is foreseeable that from the beginning of our practical work, all means will be used to fight against us. However, I now believe that a preceding public theoretical propaganda in the theological world will rather aggravate than alleviate the conflict with it. For the confession of the Spirit is, after all, ultimately a matter of will. Yes, there is a danger that our impulse will be stifled by the agitation of the press if the public learns of our will sooner than it has become action. Furthermore, it should be noted that the economic possibilities of church planting are only getting smaller and smaller, and that the financing of our movement can only really start to flow after the practical work has begun. First the spiritual reality must be really experienced, if Impulse is to awaken in the people, which help to carry and spread the religious movement. The how of starting would have to be clarified quite soon in a meeting and to ask Dr. Steiner to give us further advice in this direction.

On the question of the leadership of our movement, I would only like to emphasize here that the spiritual freedom, the initiative, and the sense of responsibility of the individual co-workers must not be impaired in any way. The ideas of threefolding will have to guide us in this.

Finally, I declare that I am willing to use my weak forces for our practical-religious goals as soon as I am free in my line of work, which will probably be the case at the beginning of June.

Otto Becher

Marienstein, February 22, 1922.

TWO TEXTS BY OTTO BECHER

This is the course of the great development of the world and of mankind: The power of the gods slowly becomes – from embodiment on earth to embodiment on earth – the power of the human being himself. Only in the distance from the gods can the human being develop independence, and only here can spiritual love arise from freedom and grow stronger. The earth is the place of the unfolding of the human ego and the human community. The true new community is based on the voluntary sacrifice of the strong. People who have awakened to the “I” are free to unite in the service of hatred and destruction, of the massification and disenchantment of the human being, or for his liberation and exaltation, for true humanity. To this kind of union above the word of Christ applies: “Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” And Paul writes to the Colossians “When Christ comes to be revealed, you also will be revealed with him.” Thus the human being experiences himself as a germinating force for a new humanity and a new earth … The development of the will must not take place without transformation and healing; there must be a readiness to receive the divine power of grace, as in the archetype of Mary, but also of Mary Magdalene. Again and again we must become aware that we can “do no works” before God. All talents have an antisocial effect as long as they are not transformed and put at the service of Christ. Not paralysis, but highest increase of impulses is connected with it; now our goals become the world goals, and the world goals become our goals. The spiritual nobility of a true priestly royalty then moves into our souls.

Today, the anxious concern is everywhere: How will a peaceful cultural construction such as this be possible? The right bringers of peace can only be those who are inflamed by true Christian impulses. A true Christian community is called to carry out into the world the new angel’s work: “Peace on earth to men of good will.

FROM THE “PFORZHEIMER KURIER” OF JULY 21, 1954:

Pastor Otto Becher died.

The Christian Community of Pforzheim lost its pastor.

Unexpectedly and suddenly, the Christian Community in Pforzheim lost its highly honored pastor, Pastor Otto Becher, after a brief serious illness. On October 31 of this year, it would have been three decades that Pastor Becher had ministered here. Born on 26.1.1891 in Holzminden, he first enjoyed a humanistic education and then studied theology and philosophy in Göttingen and Leipzig. At the age of thirty he came to anthroposophy as a constant seeker, but then found inner clarity and from this became the co-founder of the Christian Community in Germany already one year later. When he came to Pforzheim after another two years, he had soon settled in and devoted himself to this city and the circle of people he pastored with all love and intensity. His greatest and most prominent concern was to work out of silence. For the Pforzheim congregation his passing means an irreplaceable loss, since it revered him not only as a faithful intimate pastor, but also as an outstanding scholar of the humanities, as a joyful, life-loving artist, and as an excellent organizer with a talent for improvisation that was peculiar to him.

Nourishment which Endures (John 6:27)

Do not put your efforts into acquiring the perishable nourishment, but the nourishment which endures and leads to imperishable life. The Son of Man will give it to you. (John 6:27)

If there is anything that binds us to the earth, it is eating and drinking. We have hardly satisfied ourselves, and hunger and thirst are back again. They accompany our earthly life from our first breath to the last, not only in the literal but also in the figurative sense of the word. The thirst for existence is never quenched. Even when we have died, this thirst sooner or later brings us back to the earth, where we still have something to do.

Hunger and thirst also accompanied the life of Jesus Christ on earth. “I thirst”—it was one of the last words on the cross. With this prayer and the bad aftertaste of a bitter beverage He died. But also after His resurrection His hunger and thirst burn for what only we can give Him. Someone once heard Him say: “I am thirsty. I only have what I am given. I take nothing.” [*]

That is also His question to us in the enigmatic, contradictory words from the Gospel of John: “Do not put your efforts into acquiring the perishable nourishment, but the nourishment which endures and leads to imperishable life. The Son of Man will give it to you.” How can Christ ask us for something He Himself gives us?

In the language of the altar this gift, which He gives and asks at the same time, is called the communion. It is much more than a gift. It is also His entreaty: “What can you give me? Can you give yourself to me, now that I have given myself to you?”

Only if I give myself to Him is the meal He wants to share with us perfect. Only then is His thirst for our existence quenched.

–Rev. Bastiaan Baan, March 19, 2023

[*] Gabrielle Bossis, Jesus Speaking: Heart to Heart with the King, Pauline Books and Media.