For The Peoples of the World

St. Michael-Arild Rosenkrantz

For The Peoples of the World

O Christ, Thou knowest

The souls and spirits

Whose deeds have woven

Each country’s destiny.

May we who today

Share the world’s life

Find the strength and the light

Of thy servant Michael.

And our hearts be warmed

By Thy blessing, O Christ,

That our deeds may serve

The healing of peoples.

Adam Bittleston

in Meditative Prayers for Today

The Christian Community in Los Angeles now has a Patreon Site!

The Christian Community in Los Angeles now has a Patreon Site!

Rev. Rafal Nowak, the resident priest in Los Angeles, warmly invites you to explore and support a new Patreon endeavor:

On the Way to Emmaus. Talks, Ideas, Insights, Questions…

Check it out HERE

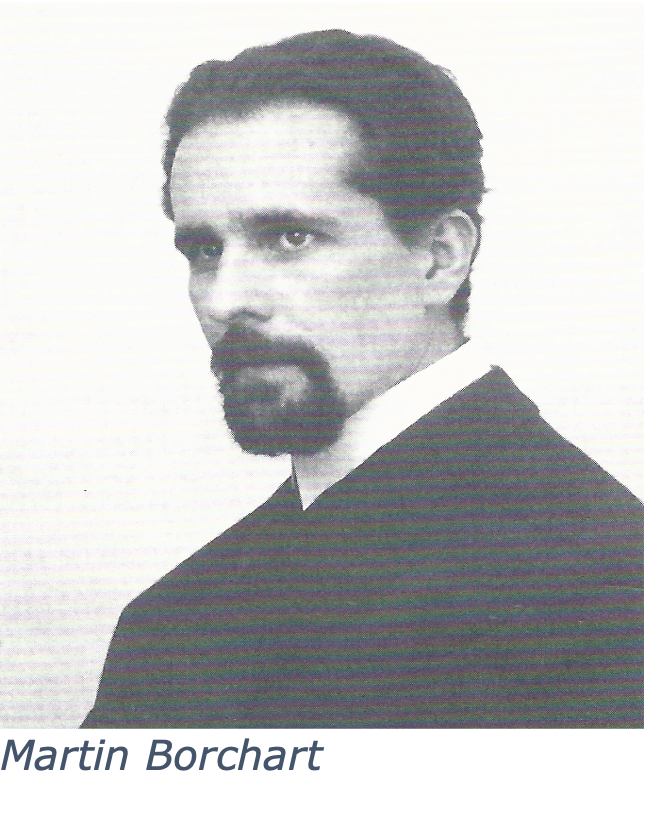

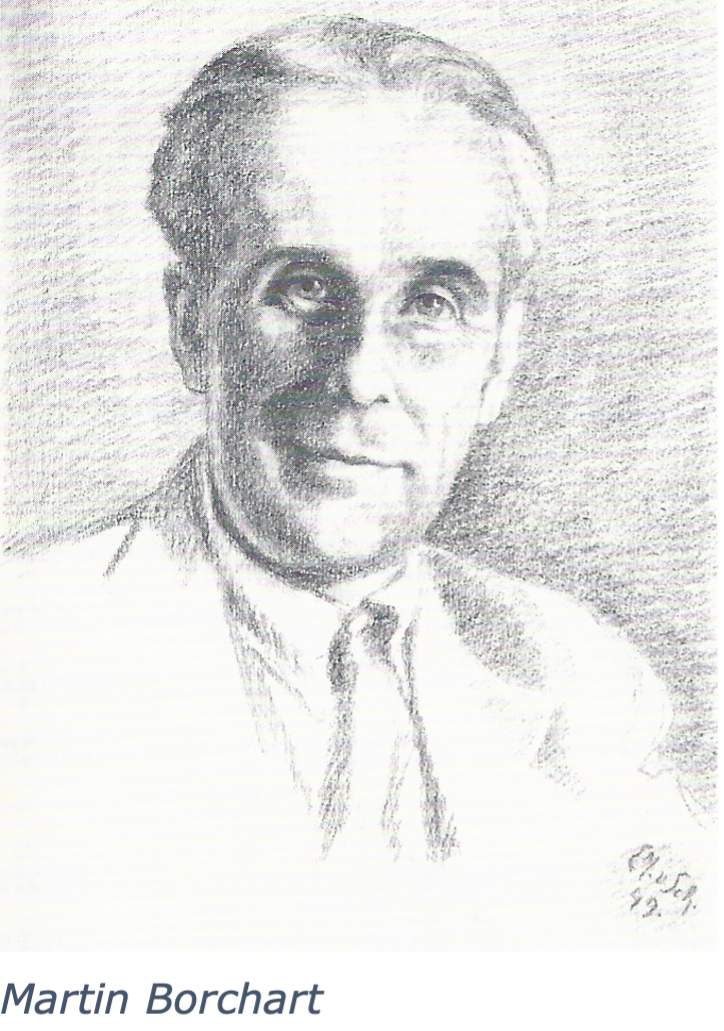

Martin Borchart

Martin Borchart

Martin Borchart

June 3, 1894, Berlin – December 19, 1971, Stuttgart

Martin Borchart, a philosophy student in Marburg, together with his wife Elisabeth, née Pappe, created the conditions for an initial inquiry to Rudolf Steiner in 1920, resulting in the founding of The Christian Community.

Martin Borchart was born in Berlin on June 3, 1894, the second son of his parents. His brother Walter was three years old at the time, and from his father’s first marriage, there was a stepsister twenty years older. His father, a principal at Berlin elementary schools, was the 39th schoolmaster of his relatives, who came from the Brandenburg area. Martin’s mother was also a teacher. She came from a Silesian estate.

Martin Borchart experienced his school days as dreary and hardly stimulating. But the buildings and schoolyards, including the school gardens, were the playground for him and his three cousins, with whom he was constantly together. His father’s school and official residence were located at Jannowitzbrücke, later at Schlesischer Bahnhof in eastern Berlin. Martin attended the Realgymnasium after elementary school. He received private lessons in Latin from a candidate of theology whom he had met in 1911 on the occasion of a summer stay on the North Sea island of Wangerooge. This was Rudolf Bultmann, the demythologizer of the Bible, who later became famous. He suggested that Martin Borchart study later in Marburg.

From his childhood, Martin Borchart reported a ‘waking dream’ in which demonic beings with frightening grimaces appeared and beset him, as he later found depicted on Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altar in Colmar in the picture of the Temptation of St. Anthony. In 1913 he passed the Abitur, which he attributed, among other things, to the fact that he had previously dreamed the subject of the German essay – “Die Weltgeschichte ist das Weltgericht” (“World History is the World Judgment”).

Although a third kind of dream was later to play an important role in his life, Martin Borchart was not a dreamer; rather, throughout his life, he maintained a particularly spiritual openness, with all alertness. His gentle humor and his fine smile were visible signs of this.

After graduating from high school, one year before the beginning of World War I, he studied theology for two semesters in Berlin. He caught up on the humanistic baccalaureate (with Greek and Hebrew). He then summed up his experience of these studies in the devastating verdict: when you become a pastor, “you take with you into practical work what you have already brought to the university in terms of religiousness, minus what you have been deprived of by studying theology.”

Right at the beginning of the First World War, he volunteered for the military, for the 4th Guards Regiment. Very soon, he suffered at the front — where he had once, as it was later discovered, been very close to Emil Bock — a first wound at Langemarck. Both legs were shot through.

Later, in Russia, he was shot through the thigh. Because of, but also despite, such weakened legs, he reported for pilot training in 1916 and was accepted. In Gotha and then in Böblingen near Stuttgart, he learned to fly the small, still rather primitive, open fighter planes, whose machine guns had to be set so that they shot precisely between the rotating propeller blades, which was not always the case.

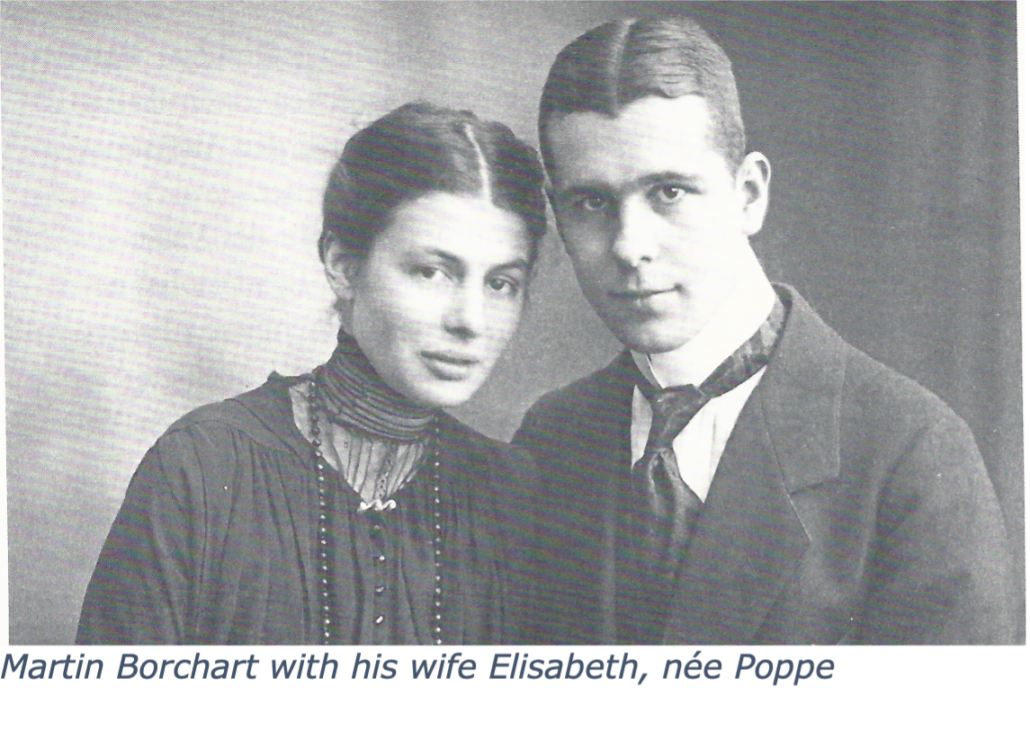

How delightfully Martin Borchart could tell about the training flight whose goal he had determined as the place of residence of the lady who was  one day to become his wife. On the flight from Böblingen to Heidenheim, he did not find the previously determined topographic landmarks in the actual landscape below. He had ‘flown astray’ and now tried to read the place name in a low-level flight over a train station; instead, he read Platform 1 and, on the next approach, Platform 2. After landing among fruit trees, he received information from a farmer that this was Goeppingen. The flight was continued, ending in Heidenheim, but because of adverse wind conditions, he landed on a field in whose immediate vicinity much later The Christian Community’s church was to be built. The couple in the house near the emergency landing site told him that Miss Poppe had unfortunately just left. They asked whether he knew, by the way, that she was an anthroposophist. While the housewife was already on the next topic — the abominable new invention of chewing gum in America, with which one could pull long strings out of the mouth— the master of the house enlightened the guest who had landed so rudely from the sky, “… the anthroposophists believe in the astral body”. The merchant and world traveler Alfred Meebold had written a book about it, The Path to the Spirit.

one day to become his wife. On the flight from Böblingen to Heidenheim, he did not find the previously determined topographic landmarks in the actual landscape below. He had ‘flown astray’ and now tried to read the place name in a low-level flight over a train station; instead, he read Platform 1 and, on the next approach, Platform 2. After landing among fruit trees, he received information from a farmer that this was Goeppingen. The flight was continued, ending in Heidenheim, but because of adverse wind conditions, he landed on a field in whose immediate vicinity much later The Christian Community’s church was to be built. The couple in the house near the emergency landing site told him that Miss Poppe had unfortunately just left. They asked whether he knew, by the way, that she was an anthroposophist. While the housewife was already on the next topic — the abominable new invention of chewing gum in America, with which one could pull long strings out of the mouth— the master of the house enlightened the guest who had landed so rudely from the sky, “… the anthroposophists believe in the astral body”. The merchant and world traveler Alfred Meebold had written a book about it, The Path to the Spirit.

From his experiences in the war as a reconnaissance pilot (from Metz), there is nothing to report further here. In January 1918, the engagement was celebrated; then, on June 18, his wedding with Elisabeth Poppe. Three children were born to the couple. Through his wife, he found access to anthroposophy. She had already, at the age of twenty-one, been accepted as a member of the Theosophical Society by Rudolf Steiner in 1912. After Martin and Elisabeth Borchart had rented a six-room apartment in Marburg/Lahn in the old town (at Marktgasse 18), lively work with like-minded people could be established in its rooms. First, they founded a local group of the League for Threefolding together with the German-American Friedrich Oehlschlegel, who was soon appointed as one of their first teachers at the newly founded Stuttgart Waldorf School. When seven people were together, they founded a branch of the Anthroposophical Society. Martin Borchart became the branch leader.

A Düsseldorf lawyer’s son and student of painting, later of theology, from Munich contacted him. It was Johannes Werner Klein with whom the following events were to take place. Both students had switched to philosophy out of disappointment in their theology studies. Together they eagerly studied Rudolf Steiner’s lectures. On Friday, January 30, 1920, in the middle of the semester, Elisabeth Borchart woke up her husband in the morning: They had to go to Dornach on Monday to visit the first Goetheanum because there could be a train accident. Since her husband hesitated, she said that he could ask Mr. Klein if he wanted to go with them. This request was made in front of the College, and afterward, Johannes Werner Klein agreed to go along; the next day Margarete Deussen joined him.

The trip was delayed. Because of incipient inflation, money had to be obtained. They took along some items for sale in Switzerland. Equipped with a membership card of the “Johannes [Goetheanum] Bau-Verein” and some issues of the house magazine of the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory in Stuttgart, the four travelers identified themselves at the consulate in Frankfurt, saying that they were welcome as students in Dornach.

A week after the idea of going to Dornach to visit the Goetheanum emerged, the four travelers had reached their destination and found that a lecture by Rudolf Steiner had been announced for the evening. (Today, this lecture of February 6, 1920, can be read in GA 196). Rudolf Steiner spoke several times about the necessity of the renewal of Christianity; that one must learn to think and act humanely, not bound to nation or tribe, as before. And then: “These things can inspire you to the question: But then what should the individual do?”

Now, in retrospect, it may seem as if those words had been spoken specifically for the new young guests from post-war Germany. In any case, Johannes Werner Klein felt inspired to ask Rudolf Steiner for an appointment, which took place on Sunday, February 8 [compare the chapter on J. W. Klein]. Rudolf Steiner noticed during this conversation that Johannes Werner Klein had not quite understood him and therefore asked for his companion, Martin Borchart; if he had a question, he would be available for him. Martin Borchart knew nothing of the content of the conversation that had just taken place between Rudolf Steiner and Johannes Werner Klein and had no question of his own. Borchart had already discussed his doctoral thesis with Rudolf Steiner and had also received a topic for it, which unfortunately has not been passed down; it did not materialize later because of the founding of The Christian Community.

However, the question about the third church, about Johannine Christianity and its religious form, was raised by Johannes Werner Klein (following the thoughts of the philosopher F.W. Schelling in his Philosophy of Revelation). This was followed up on later. Almost a year and a half had to pass before, again with Martin Borchart’s help, the correctly formulated request of a group to Rudolf Steiner made possible the promise of a first course oriented toward religious renewal. At that time, on May 22, 1921, when they were struggling for the right formulation of this request, Martin Borchart had just the day before acquired a newly published lecture cycle by Rudolf Steiner. During the night, he immediately studied the first three lectures (“Cosmic and Human Metamorphosis,” today in the Complete Edition Nr. 175: Building Stones to a Knowledge of the Mystery of Golgotha). More than four years earlier, on February 20, 1917, Rudolf Steiner had stated in Berlin, in the presence of Friedrich Rittelmeyer, the necessary distinction between spirit-cognition (anthroposophy) and religious practice. Spirit-consciousness is kindled through religious practice, and spirit-knowledge is acquired through anthroposophy. Martin Borchart spontaneously grasped this distinction at that time. He conveyed this quotation to Gottfried Husemann, who then succeeded in formulating the question about new forms of Christian religious practice. Thus, also through Martin Borchart’s contribution, the “June Course” for the preparatory group of eighteen students in Stuttgart became possible. From then on, he was a witness at all stages of the founding of The Christian Community.

On September 16, 1922, at the age of twenty-eight, he was ordained to the priesthood by Emil Bock. He actually wanted to go to Bremen, where he had hoped for help from an uncle to found a congregation there. However, he left this city to his friend Johannes Werner Klein and became the founder of the congregation in Dresden (1922), then in Bayreuth (1924), before becoming pastor in the Stuttgart congregation in 1925, where he found the center for all his further activities.

On September 16, 1922, at the age of twenty-eight, he was ordained to the priesthood by Emil Bock. He actually wanted to go to Bremen, where he had hoped for help from an uncle to found a congregation there. However, he left this city to his friend Johannes Werner Klein and became the founder of the congregation in Dresden (1922), then in Bayreuth (1924), before becoming pastor in the Stuttgart congregation in 1925, where he found the center for all his further activities.

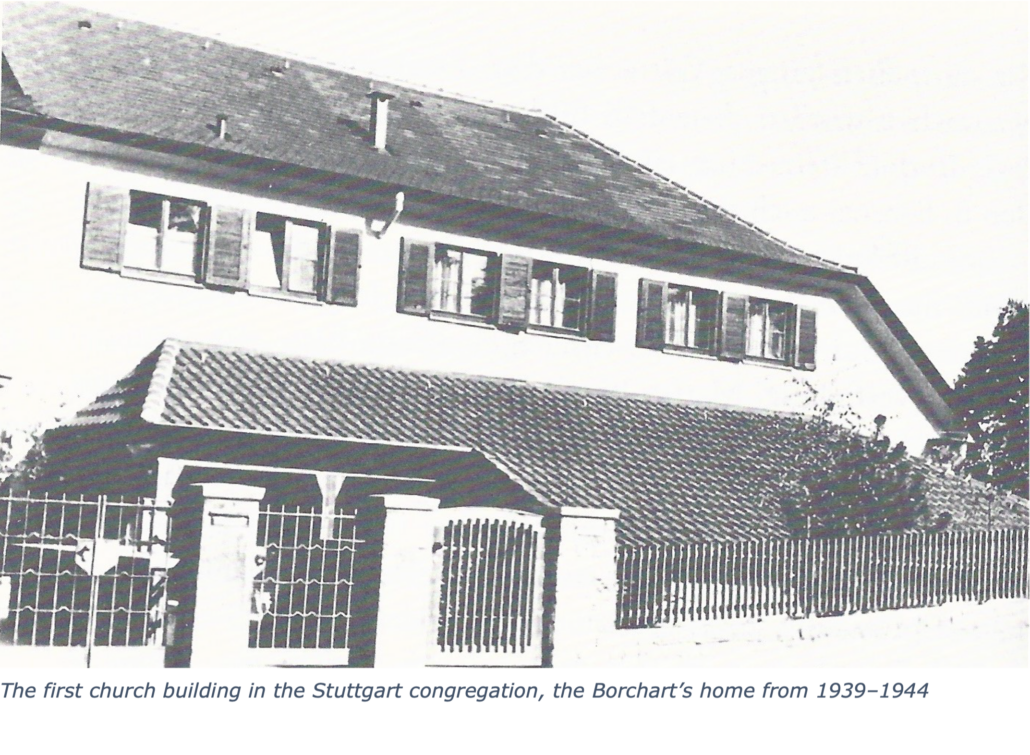

From then on, Martin Borchart worked as a priest in the Stuttgart congregation with Kurt von Wistinghausen, Erwin Schühle, Arnold Goebel, Friedrich Rittelmeyer, Emil Bock, Hermann Beckh, and many other colleagues who were only active there for a short time. In 1933 he was able to live with his family in the newly built seminary house. In 1940, however, human relations with Mr. and Mrs. Husemann, who lived in the seminary, made it seem more favorable for him and his family to move into the parish house in the Werfmershalde, into the apartment above the consecration room. From 1937 on, he suffered from the consequences of a motorcycle accident.

In 1938, after Friedrich Rittelmeyer’s death, Martin Borchart was appointed Lenker for Stuttgart and the Württemberg Swabian communities. This was followed by the banning of The Christian Community by the National Socialists on June 9, 1941, and several weeks of imprisonment in the Welzheim concentration camp. During the prohibition period, he prepared for an interpreter’s examination in English and Russian in Heidelberg but, for unknown reasons, did not take the final examination. Instead, in October 1942, he joined the Stuttgart office of the Central Dairy Kuhn, Rottenburg/Neckar, as office manager, personnel supervisor, and public relations officer. During the fire in the community center in 1944, he contracted severe smoke poisoning; from then on he suffered from respiratory problems.

In 1938, after Friedrich Rittelmeyer’s death, Martin Borchart was appointed Lenker for Stuttgart and the Württemberg Swabian communities. This was followed by the banning of The Christian Community by the National Socialists on June 9, 1941, and several weeks of imprisonment in the Welzheim concentration camp. During the prohibition period, he prepared for an interpreter’s examination in English and Russian in Heidelberg but, for unknown reasons, did not take the final examination. Instead, in October 1942, he joined the Stuttgart office of the Central Dairy Kuhn, Rottenburg/Neckar, as office manager, personnel supervisor, and public relations officer. During the fire in the community center in 1944, he contracted severe smoke poisoning; from then on he suffered from respiratory problems.

In former times, he had been called ‘the handsome Martin.’ The tall, slender figure, leaning a little on his cane with the silver knob, a fine smile on his face: this is how the Stuttgart community experienced him as their priest for many decades.

A special concern of his was the annual conference of the Swabian communities. The people should get together from many places and experience The Christian Community. On the occasion of such a conference in 1965, the Swabian Building Fund was founded, a free economic association of the congregations for the financing of church buildings. Thus, for example, the congregations in Esslingen, Ulm, Murrhardt, Tübingen, Stuttgart, and Überlingen were able to build their churches. Thanks to this joint institution, many church centers have been built to this day.

Within the circle of priests of his lenkership and under his free and benevolent gaze, a fraternal common ground around the need for Honorarium requirements was able to unfold in the form of the first salary network in The Christian Community. From this side, the germs of new social forms were sown.

For decades Martin Borchart had to bear the brunt of the character of his founding colleague Gottfried Husemann, who died remarkably close to him. Martin was almost always silent, rarely and only quietly voicing his opinion. He lives in memory with the smile of a mildness that only borne pain makes possible; he could rejoice royally over what his pastor colleagues achieved, especially the younger ones.

Thus, in the last years of his life, he could often be heard saying gratefully and joyfully: “Lord, now you let your servant go in peace.” He died on the fourth Sunday of Advent, December 19, 1971, in Stuttgart, a few months after the death of his son Heinz, who had also become a priest. His crossing of the threshold led him directly into the days of the Christmas events. The Christian Community owes to his selflessness the decisive act of mediation in the hour of its foundation.

MEMORANDUM

The realization that a renewal of religious life was necessary for the salutary progress of humankind, and the will to help in this, brought together the participants of the Stuttgart Theology Course in June 1921. These young theologians were of the opinion that the theological faculty could not give them a fruitful preparation for their goal, and a state-church office could not give them the right field for their work. Therefore they turned to Dr. Steiner to receive from him what anthroposophy could give them to prepare them to found viable Christian communities. Practically, the work of financing was immediately set in motion at that time, which was to create a basis for making the spiritual work possible. Since a certain financial basis now seems to have been created which could support our work in the beginning, and since many signs in the present seem to me to indicate that we would be fulfilling a time requirement if our work were to begin now, and that perhaps the appropriate period could be missed by prolonged hesitation, it seems to me necessary that those should come together who are willing to put their full strength into it at once. An educational course led by Dr. Steiner, seems to me to be an indispensable prerequisite. I can overcome the consciousness of my inadequacy and unworthiness only by hoping to grow through the great cause. And so I now want to stand up for it completely, giving up my previous work.

-Martin Borchart

Heinrich Ogilvie

Die Gruender der Christengemeinschaft: Ein Schicksalsnetz

By Rudolf F. Gaedeke

Translated by Cindy Hindes

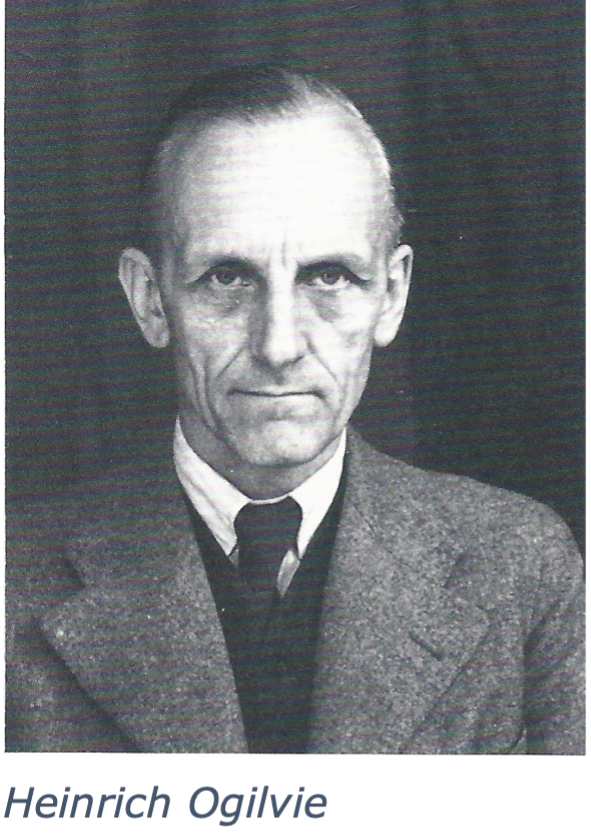

Heinrich Ogilvie

Heinrich Ogilvie

July 18, 1893, Schleusingen – February 15, 1988, Zeist

Heinrich Ogilvie’s father was supposed to have taken over the administration of at least one of the family estates in the Memelland. For this purpose, he had studied and graduated in law. However, shortly after he took over the administration, he voluntarily renounced his inheritance in favor of his younger brother, who did not yet have a profession. He then became a lawyer in the small Thuringian town of Schleusingen and married the daughter of the local high school principal.

Heinrich Ogilvie was born in Schleusingen on July 18, 1893, the third of eight children. Two siblings died early. As the eldest surviving son, Heinrich Ogilvie received a particularly strict upbringing in keeping with family tradition. A weakness in the little child’s back caused the doctor to prescribe a two-year bed rest treatment. The boy was also often sick, and, in some cases, had repeated childhood illnesses. He was so weak in elementary school, that he was considered a dreamer and was tormented by his comrades. For example, they repeatedly pressed him crosswise against a wall. Finally, on one such occasion, he managed to stage a powerful outburst of anger, with which he was able to send his classmates fleeing.

In him, who on his father’s side came from an old Scottish noble family, there lived an overpowering soul of will, but also of passions, as he himself described it in the small booklet of his memoirs, Jakob, wo bist du [Jacob, Where Are You]?

He fared better in high school. The teachers and the subject matter didn’t appeal to him very much, but the circumstances seemed more humane because the director was his mother’s grandfather.

An overwhelmingly painful stroke of destiny came into his childhood life with the news of his mother’s death, which reached the twelve-year-old Heinrich during summer vacation on the island of Föhr. Now the world of childhood perished, and another world appeared on the horizon of consciousness. He wanted to turn toward it. Now it was clear to him: I want to become a pastor! Every Sunday, he went to the Lutheran church with his grandfather. But after age fourteen, distress, doubts, and the passions of the “wild blood” of the ancestors increased in his soul.

For a year, the fifteen-year-old was preoccupied with Lenau’s epic The Albigensians with its impressive description of the so-called heretics. At sixteen, he was fascinated by the Epistle to the Galatians from the New Testament because he found in it the motif of the freedom of human conscience as he understood it. In the same year, however, his beloved and revered grandfather was snatched from him (1909). It was the second death in his young life that marked his soul.

Now Heinrich founded a literary students’ association. He read poems — on one evening, for example, by Goethe – but not before he had read all of Goethe’s poems for himself and selected those that were important to him. Schiller’s dramas, as well as many others, were treated in the same way. The young man had now become also physically stronger. He practiced a lot of sports: gymnastics, competitive swimming, and soccer.

In 1911 at eighteen, Heinrich Ogilvie graduated from high school and immediately began to study theology (in Halle an der Saale, among other places). He also read philosophy, psychology, politics, and art history. However, doubts about everything that had been handed down, ignited by an article by Johannes Müller (“Glaube und Wissen” [Faith and Knowledge]), pressed him hard. But when the World War broke out in 1914, he hoped to escape this world of doubt and bleak meaninglessness by dying in a hail of bullets.

A third time he looked death in the eye: it was a wound he had to endure. A sniper’s bullet had shattered his thigh while he was transporting a wounded comrade. After eight months in the hospital, the twenty-one-year-old had to learn to live with the fact of his disability. Nevertheless, he was able to take his theological state examination during this time.

Finally, however, he was drafted again as a guard soldier. The most important event of this second period of military service for him was his comradeship with a very simple Catholic soldier from Baden, in whom he experienced the self-evident religiosity and faith, from which he himself was meanwhile so very distant. He wrote: “In the primal goodness and love, in the freedom and irresistible truthfulness of his being, I saw the reality of Christ in a man. Now I knew that the Son of Man had lived and was still alive. Life on earth has a meaning. There is an overcoming of decadence. Gradually, I saw in more and more people that which is of Christ or what is waiting for Him. It was possible to live and work for that.”

Finally, however, he was drafted again as a guard soldier. The most important event of this second period of military service for him was his comradeship with a very simple Catholic soldier from Baden, in whom he experienced the self-evident religiosity and faith, from which he himself was meanwhile so very distant. He wrote: “In the primal goodness and love, in the freedom and irresistible truthfulness of his being, I saw the reality of Christ in a man. Now I knew that the Son of Man had lived and was still alive. Life on earth has a meaning. There is an overcoming of decadence. Gradually, I saw in more and more people that which is of Christ or what is waiting for Him. It was possible to live and work for that.”

After the end of the war, he took over the leadership of a kind of student residential community, the “Tholuk-Konvikt” in Halle an der Saale. In 1919 he passed the first and, in 1921, the second examinations and was thus a candidate for the ministry. But he did not want to take on a pastorate. He wanted to be socially active. In fact, he wanted to renew the whole of culture. He founded a country home for needy young men with that Catholic comrade.

To get to know agriculture, he hired out as a farmhand to a farmer in the Saale Valley. During this time, he became engaged to Margarete Schulze, an elementary school teacher, who was to accompany him for many decades as a faithful wife and mother of four children. Another time, Heinrich Ogilvie was in the village Redentin near Wismar in Mecklenburg to run – all by himself – a small, rather neglected farm. During this time, Rudolf Steiner’s book How to Know Higher Worlds came into his hands. He read it up to the middle but then put it aside with the verdict: “It is excellent, but it is not for me.”

There in Redentin, suddenly, unannounced, a strange student stood in front of him in the stable. It was the summer of 1921. Gottfried Husemann had set out on his journey after the “June Course.” Among other addresses, he also had Heinrich Ogilvie’s with him, which he had received from Arnold Goebel and Waldemar Mickisch. Gottfried Husemann, the foreign student, invited Heinrich Ogilvie to come to the “Autumn Course” in Dornach. But the latter did not want to know anything about it and sent him away. Just then, his fiancee came along and said, “Bring him back, bring him back, join them, this is your path!” But Heinrich Ogilvie did not do it.

He was asked in Marburg/Lahn to take over the leadership of a “social work-community” and establish a rural folk high school in the spirit of the ideas of Sigmund Schulze and his “Sozialen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Berlin-Ost”. Three professors, among them Paul Natorp and Rudolf Otto, acted as promoters of this enterprise.

Rudolf Otto wanted Heinrich Ogilvie to be the secretary of his “World Federation of Religions.” Ogilvie also rejected this. His ideal, which he wanted to serve, was: Everything in life should become a sacrament.

At Easter 1922, he became director of the Municipal Adult Education Center in Kassel. Quakers had provided a salary of thirty thousand marks for three months in advance. (There was inflation.) With this security, Heinrich Ogilvie thought he could marry. On April 12, 1922, his father’s seventieth birthday, the civil marriage took place. Three days later, his father died suddenly. Again, death was closely connected with a major step in his destiny. The marriage produced three sons and a daughter.

After the meeting of those who had decided to found The Christian Community in Berlin in March 1922, Richard Gitzke went to Kassel to prepare for the formation of a congregation there. He also appeared at the Volkshochschule [folk high school] of Kassel and invited Heinrich Ogilvie to attend his two lectures.

In the previous winter of 1921/22, Heinrich Ogilvie had first experienced Rudolf Steiner at his lecture given in Frankfurt. Ogilvie noticed on the train ride back at night to Marburg that in discussion with other listeners, he defended Rudolf Steiner, although the lecture had given him nothing, as he thought. Then, in Kassel, it was similar. Heinrich Ogilvie attended Richard Gitzke’s lectures and found himself in the role of the interpreter in the subsequent discussions, without having connected with anything that was said.

Heinrich Ogilvie did not want to become a member of the religious renewal movement. But there must be something to learn in the group, he thought. Therefore he wanted to get to know these people. He went to Breitbrunn. The people of the circle and most of what they said seemed strange to him. He had to endure severe trials of the soul and transformations: “A presentation by Harald Schilling on “Workers and Destiny” overturned my whole socialism.”

Toward the end of the meeting, he decided to go to Dornach to co-found The Christian Community. Now it was clear to him that “an objective religious life in cultus and sacrament creates foundations also for the solution of the social question.” He asked his wife by telegraph to come to Breitbrunn; she was to be involved in the decision. She then told him: “I told you right away that this is your path. Of course, I will go with you. But we should not have married, for you must be unmarried.”

By the end of the weeks in Breitbrunn, Heinrich Ogilvie had canceled the pastoral care of communist workers that he had already promised to some factory owners in Zeitz, Saxony. Now he was free for “the cause.” The will that had long before animated the twelve-year-old at the death of his mother was fulfilled. On September 16, he was ordained by Emil Bock and then sent out as a pastor of The Christian Community.

He wanted to found a congregation in Dortmund. A proper room could not be found – only a small chamber in Annen with a widow who had given birth to twenty-two children. Every morning he drove to Witten to work ten hours a day as a hauler. But his health could not stand this for more than half a year: “Dust lung” forced him to stop. After discussions, lectures, and courses, however, first a human basis and then also a financial basis for community work arose. It still took a whole year before the first Consecration Service could be held in Dortmund in the fall of 1923.

Despite all the difficulties that had to be overcome everywhere when the first congregations were founded at that time, five of the founders had to struggle with particular obstacles: Herman Groh, also Wolfgang Schickler in Essen, Walter Gradenwitz in Düsseldorf, Gottfried Husemann in Cologne and Heinrich Ogilvie in Dortmund.

For Heinrich Ogilvie, this first period of pioneering work lasted until the spring of 1925, when his strength was exhausted. He recuperated in the sanatorium run by anthroposophical doctors in Gnadenwald near Hall in Tyrol and then in Breitbrunn on Lake Ammersee in Upper Bavaria, where he was a guest of Margareta Morgenstern and Michael Bauer. He regained the health that allowed him to accept the request to move to the Netherlands to found The Christian Community there.

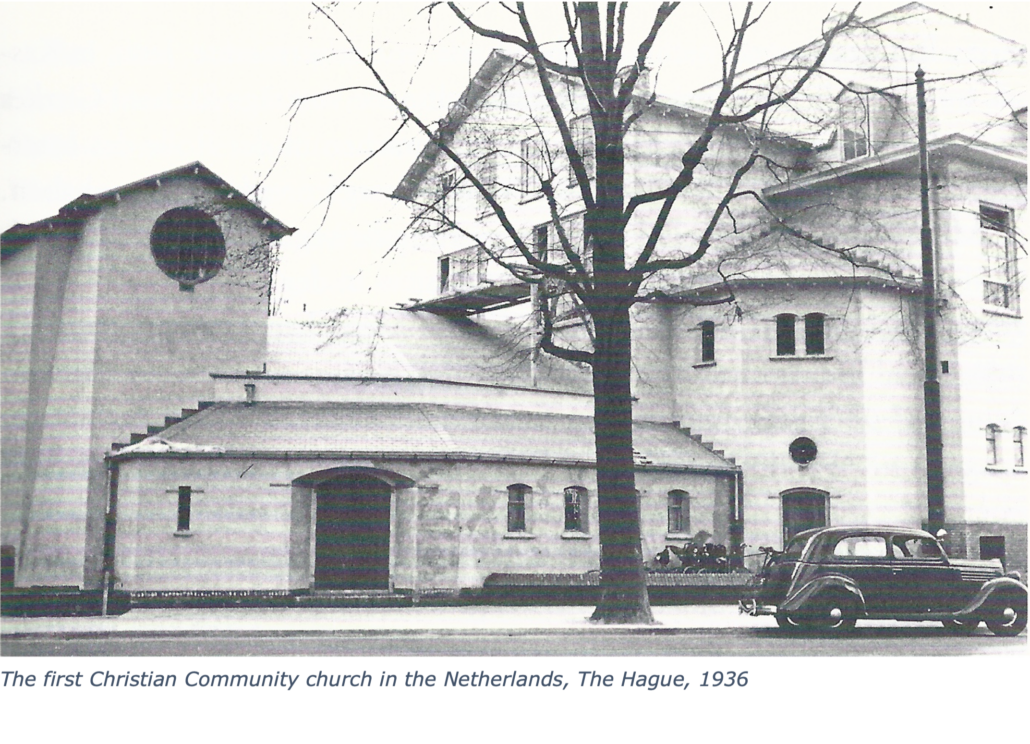

After Emil Bock’s first visit to the Netherlands in November 1924, a preparatory group for the founding of The Christian Community had formed in The Hague. The group invited him to lecture again in November 1925. On this occasion, Emil Bock baptized two children, and the Dutchmen Ludovicus Mirandolle, Gerrit Gerretsen, and Cornelis Los decided to seek the priesthood. As early as January 1926, Emil Bock again traveled to the Netherlands together with Friedrich Rittelmeyer and Heinrich Ogilvie. In addition to lectures, Rittelmeyer held the first Consecration of the Human Being in a small circle on February 7, 1926. On Palm Sunday 1926, the first Consecration Service was publicly celebrated by Emil Bock in The Hague and simultaneously by Heinrich Ogilvie in Amsterdam. The latter decided to stay in the Netherlands and took care of the translation of the text of the Consecration Service, together with the three aforementioned Dutchmen and Jeanne Brunier. As a result, on St. John’s Day 1926 in The Hague, Ogilvie celebrated the first Consecration Service in Dutch.

In the following months, he prepared the founding of congregations also in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. The founding in The Hague occurred on November 13, 1926, with 20 people. Initially, celebrations were held in a private house. The later co-workers, Ludovicus Mirandolle, Gerrit A. Gerretsen, and Cornelis Los, were actively involved in this first community established outside the German-speaking area. After Gerretsen’s and Los’s ordinations on December 19, 1926, Heinrich Ogilvie moved to Amsterdam, where community life was concentrated in the house at Johannes-Verhulststraat 41 for many years, starting in 1930.

In the 1930s, Heinrich Ogilvie filled in for Gottfried Husemann’s Lenker activities in the Ruhr region before he himself was given the Lenker’s office in 1938. In 1935, The Christian Community was officially recognized as a church in the Netherlands by the Dutch Ministry of Justice. In the same year, the congregation was able to move into the very first room it had constructed for the sacraments. When the National Socialists (Nazis) occupied the Netherlands in 1940 during the Second World War, outer conditions were oppressive but strengthening for the community: The congregation in Amsterdam also had forty Jewish members. In 1941 Heinrich Ogilvie was banned from working. However, a high police officer named Ogilvie – a sixth cousin – repeatedly allowed the personnel file to disappear at the bottom of the mountain of files.

In 1945, his community work and his Lenker activity from 1938 could be taken up again publicly. In Amsterdam, the purchase of a house was possible. In 1948 the well-known conference center “Land en Bosch” was built, where many children’s and youth camps, conferences, meetings, and synods took place over several decades. In 1956 the retirement home Valckenbosch was opened in Zeist, and in the following decade, the three impressive church buildings in Zeist, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam.

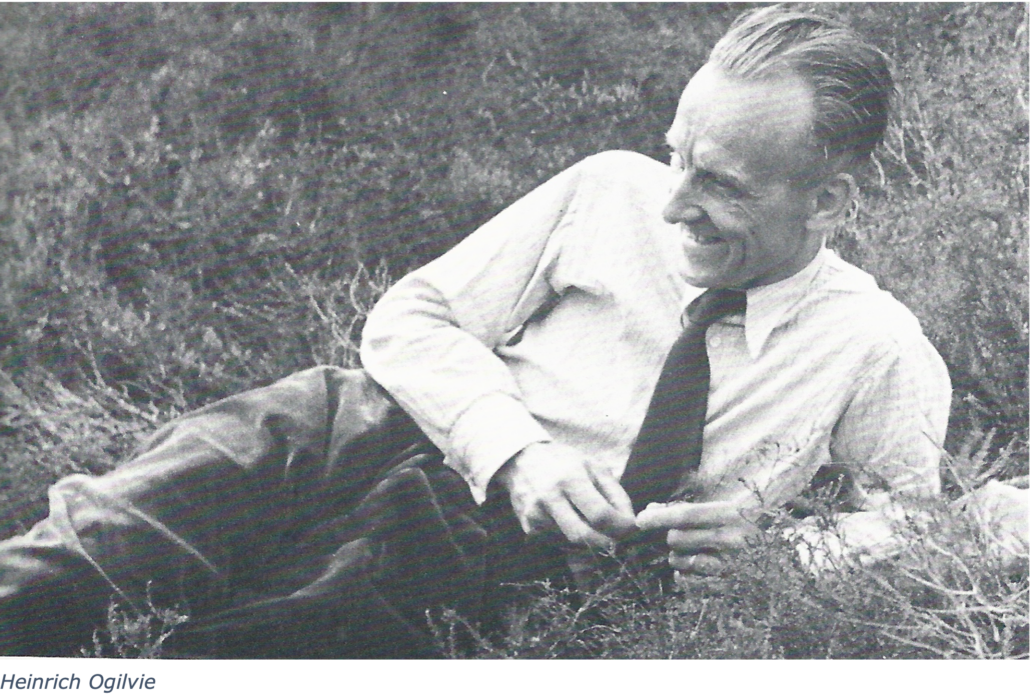

As a result of a serious accident in 1956, in which Ogilvie re-injured the leg wounded in World War I, he had to endure severe pain for eight months – deliberately without narcotics. Annual recuperative stays in Switzerland and many trips to almost all European countries and the Near East were also part of his life. Especially appreciated is his translation work. Ogilvie is to be thanked for a complete translation of the New Testament into Dutch and, in the last years of his life, into German.

With his wife, he moved to the retirement home in Valckenbosch. After her death, Heinrich Ogilvie continued to work there with unbroken alertness and his willful spontaneous temperament until he died in Zeist on February 15, 1988 – a pioneer of The Christian Community of a very original kind.

Camp Harmony Lake is Raising Funds!

Dear Christian Community Friends,

I hope this letter finds you enjoying a beautiful St. John’s Tide!

I am writing to ask if you might consider supporting a child to attend The Christian Community Camp Harmony Lake this summer. The camp, which has thrived for 22 years under the directorship of Rev. Carol Kelly, and is celebrating a 50th anniversary this summer, has been an anchor in the lives of many young people as they move from camper to counselor to supporter. It is truly a work towards the future in this way, and one that is filled with love, friendship, abiding connection and support of young people connected to our movement of religious renewal.

This summer, the camp finds itself in a challenging time. It was forced to close during Covid-19, and it lost its home in Maine. It is now reopening in a beautiful spot in PA, and slowly recovering momentum. Many of the children enrolled are in families who are unable to pay the fees in this time of recession and strain. But we have not turned them away!

We are asking those who can, to donate to cover the cost, or part of the cost, for a child to attend camp this summer. The cost for one child is $1,600. We need to raise scholarship funds to cover 10 children to attend camp.

Please know that your contribution will provide lasting support for a young person from one of our communities to experience the respite, love, spiritual sustenance and connectedness of The Christian Community in a difficult time.

Please make checks out to The Christian Community Camp and mail to 10 Green River Lane; Hillsdale, NY 12529, attn Carol Kelly. Please write camp scholarship in the memo line.

Donations to the camp are tax deductible.

Many Thanks and Blessings,

Faith DiVecchio

On behalf of Revs. Carol Kelly, Anna Silber and the Camp Harmony Lake team.

Flame

Every human being has a flame, that must not be quenched. Perhaps we should really say: Every human being is a flame, that must never be quenched. This is the flame with which we come out of the fire of the spirit when we are born. It is the greatest art of all to keep this fire burning our whole life long—not only in joy, but also in grief; not only in strength, but also in weakness. Also when you are sick, even if you are mortally ill, the fire can still smolder under the ashes.

There are, however, countless ways to choke this flame and extinguish it. The material world can make a slave of us, a slave of money and possessions, of power and violence, of intoxication and addiction, which make us forget what our task is in this life.

John, the greatest among all human beings, fore-lived, fore-suffered, and fore-died for us how we can keep the inner fire burning. Always, down to our time today, he has been “the burning and shining lamp” (Jn. 5:35), who gives us a radiant example of how we can preserve our flame. In one word John sums up what we need to do: Metanoeite, which means: Change your hearts and minds. (Mt. 3:2) This flame word tells us: Do not stop moving on the way. The flame can only keep burning if every time again you dare leave behind whatever threatens to chain you to the dying earth existence. With this disposition you will one day rise out of the ashes like a Phoenix.

Metanoeite:

Mensch, so du etwas bist Human Being, if you are truly something,

So bleib ja nur nicht stille stehen. Then do not stay there standing still.

Man muss von einem Licht From one light you must go

Fort in das andere gehen. Forth to the other light.

(Angelus Silesius)

–Rev. Bastiaan Baan, July 9, 2023

“He must increase, I must decrease.”

The ego is the shadow of a great light. In a world where egoism reigns supreme we often imagine: the ego, that am I.

But if that is the only reality, what is then left of us at the end of our life? When someone becomes old and decrepit, gradually all the capacities disappear on which our ego is based. Nothing happens of itself anymore, until we eventually become dependent on the help of other people. The light of self-consciousness weakens, flickers, and goes out. What is then left of us?

What is left on earth is what we call the mortal remains, an empty husk that soon falls apart. Earth to earth; ash to ash.

But death is much more than the inglorious end of life on earth. It is the time when the wheat is separated from the chaff. As the shadow of the ego fades, the light of the Spirit grows. Christ stands at every deathbed and receives the harvest of every human life. Only then does the dying person recognize: Christ is the light of my shadow.

Countless people live as if there will never be an end to their ego, until the irrevocability of the end of life cannot be ignored anymore and there is no longer a way back—only forward, through the eye of the needle.

We don’t need to wait for that moment. We can also try, in the midst of life while we are fully engaged in our everyday existence, to begin to walk this way forward. Then we begin to realize: I am very small, and the world that stands behind me is very large. The greatest of all people on earth, who became the smallest of all, let the light of his shadow manifest with the words: “He must increase, I must decrease.”

Then only, if these words are fulfilled in life and death, is the promise fulfilled: “Christ in me.”

Rev. Bastiaan Baan, July 3, 2023.

St. John’s Tide

“From You come light and strength,

To You stream love and thanks.”

These two sentences from a children’s prayer[1] encompass everything that is divine service and human service—or rather, should be.

God serves His creation ceaselessly with light and strength. Not only the inexhaustible light of the sun and the life forces of nature, but also the light of our consciousness and our life forces—we owe it all to Him. God’s religion—that is His creation.

The only appropriate answer to this gift is love and thankfulness.

Light and strength from God—love and thankfulness from the human being. That is the golden chain that connects us with each other.

As long as humanity has been conscious of its origin and future, people have served God with this answer at all the altars on earth. Perhaps this time, our era, is the only one in the history of humanity in which it is no longer self-evident to serve God in this way. We no longer realize to whom or what we owe the light of our consciousness and our life forces.

Our sciences teach us that the laws of physics and chemistry carry and order life on earth. Our daily existence is the product of these sciences, which teach us to act quickly, efficiently, purposefully, and especially to make a profit on everything. But if love for God and thankfulness to God die out on earth, the golden chain is broken. What will then happen on earth?

Are we perhaps already seeing the consequences of our lovelessness and our thanklessness in the mirror of nature, which is falling into chaos? Or is nature, God’s creation, His answer to the chain that is broken?

Be that as it may, if there is anything that is lacking in our chaotic era, it has to be our answer of love and thankfulness. And if this answer does not come from all of us, as it did as of old, then at least from some places on earth where individuals gather at the altar to profess with heart and soul:

“To the Father God shall stream our soul’s devoted and heart-warm thanks.”[2]

-Rev. Bastiaan Baan, June 2023

[1] Verse for the children in the first grade of the Waldorf School.

[2] From the Epistle of St. John’s Tide.