Herman Groh – 11 June 1894, Berlin – 14 December 1957

Herman Groh was a man of the world who broadened his education throughout his life. He spoke many languages and understood several more. Outwardly, Groh’s life took him first to Russia, Siberia, and Vladivostok during the First World War, and then (1928) to California for 6 months. In other words, he traveled from East to West before settling in the center, where he focused his energies. This also seems to correspond to the major inward gesture of his life.

Herman Groh was a man of the world who broadened his education throughout his life. He spoke many languages and understood several more. Outwardly, Groh’s life took him first to Russia, Siberia, and Vladivostok during the First World War, and then (1928) to California for 6 months. In other words, he traveled from East to West before settling in the center, where he focused his energies. This also seems to correspond to the major inward gesture of his life.

Born into a Berlin merchant family in Berlin-Charlottenburg on 11 June 1894, Groh attended a grammar school in Cologne from Easter 1901 until his graduation at Easter 1912, receiving a comprehensive education with an emphasis on classical languages. Already at this age, he read philosophical books and Shakespeare during class. He exercised his lanky body with iron discipline and became the top athlete in his class. He went on long hikes with his comrades, becoming well-acquainted with the environs of Berlin and the Brandenburg region. Given the number of kilometers covered, they were really more like marches than hikes. His gym teacher, Döhring, not only took his boys out into nature, but in the evenings after the hikes also enthusiastically introduced them to the world of idealistic philosophy and classical literature.

Groh reportedly nearly drowned around this time while swimming in the Müggelsee (a lake outside Berlin). He saw his entire life up to that moment pass before him in full detail. During the same timeframe, while playing ice hockey on a frozen lake, he once saved the life of someone who had broken through the ice.

He passed his high school graduation exams at 18 and a half, later explaining that this was thanks to his A in gymnastics. Before the First World War broke out, he completed a voluntary one-year tour with the cavalry in Schleswig and began his studies in Freiburg/Breisgau, studying philosophy and political economics. He became particularly engrossed with Hegel.

Drafted at the outset of the war, he was a 21-year-old junior cavalry officer in Russia when he was captured in 1915 during a patrol in Courland. It was not until January 1921 that he returned home (via China) after a long Russian captivity.

His time as a prisoner-of-war in Siberia, and then ultimately as an able-bodied citizen under the “Reds” brought him many “opportunities”—for example as a lumberjack or as a librarian in Minussinsk—a calmer phase in a compound in Krasnoyarsk. He was able to continue his Hegel studies there, and this brought him into contact with the epistemological writings of Carl Unger and books by Rudolf Steiner. (The books had been sent to a comrade by a friend from Vienna). The book How to Know Higher Worlds impressed him the most, and it was after reading it that Groh decided to return to Germany to meet Rudolf Steiner, although he had actually intended to remain in Russia.

Even before this calmer chapter during the turmoil of revolutionary Russia, Groh had faced death a second time: Having escaped from a camp with a friend and walked 2,000 kms through Manchuria, he was captured in the last town before the Chinese border and imprisoned. The “Reds” released him shortly before he was shot: just before his execution the news of the tsar’s assassination arrived. Following his release from captivity in Vladivostok and his return to Europe by steamship, Groh met a group of students from Tübingen travelling for the anthroposophical First Class course in Stuttgart in 1921. Among them was Gerhard Klein, who later became his brother-in-law. His first question to them was reportedly about whether there was a real community here. He became one of the participants in the so-called Autumn Course, the second major round of teaching for the founding circle, to which Rudolf Steiner had invited people to Dornach.

Without finishing his studies or professional training, Groh committed himself to this common goal. In 1922, he reportedly made most of the journey from Berlin to Breitbrunn on foot, as simply driving to such an important event was out of the question. Unfortunately, he is missing from the Breitbrunn group picture. He then drove with the others to Dornach and was ordained by Emil Bock in the first Goetheanum on 16 September 1922 as the 21st member of the circle.

Herman Groh founded his first congregation in Essen-Mülheim. He chose this city because there were hardly any anthroposophists, thus also no branch of the Anthroposophical Society. He then worked in Vienna starting in 1929, setting up a small chapel in his home in Grinzing. During this time, he heard Dr. Roman Boos make serious attacks on The Christian Community, which shocked him deeply. Finally, as of 1935, he worked in the Dresden congregation for his third sending.

After participating in Rudolf Steiner’s last major lecture in Dornach in September 1924, he was married there on 26 September to his colleague Gerhard Klein’s sister Lilli. Alfred Heidenreich celebrated the marriage sacrament in the White Hall of the first Goetheanum. Gottfried Husemann and Marta Heimeran were witnesses and five other colleagues were present. The couple had six children.

In 1939 in Dresden, before The Christian Community was banned, Groh was drafted into the Wehrmacht at the beginning of the Second World War, even though he was already 45. Due to his excellent language skills, he was transferred on the recommendation of his brother-in-law Gerhard Klein from a veterinary hospital for horses to the large prison camp Mühlberg/Elbe as an interpreter for Russian, English, and French. He cultivated extensive connections with the captured Russians and Frenchmen. Instead of carrying a revolver for his personal security, he carried his sandwich with him when he had to accompany the prisoners. A prison chaplain later called him a “true Christian”; that is what he proved to be there. Johannes Lenz wrote about this time in more detail in the journal Die Christengemeinschaft, 2004, p. 579ff. When a typhus epidemic broke out in the camp and all the Germans decamped, he remained steadfastly at his post until he caught the disease himself.

As the person responsible for all church services in the camp, he worked closely with clergy of all denominations from a multitude of countries. With the help of a Russian clergyman who had been captured by the Germans while serving as a French soldier, Groh translated the Consecration of the Human Being into Russian.

After his recovery from typhus, he was released from service in 1944—again based on a recommendation—when his father fell seriously ill. Then he was obliged to manage his father’s chain of stores “Groh Brothers Milk and Cheese,” with all its products and dairies. While thus occupied, he experienced the collapse of the Third Reich in Berlin. The war had barely ended when Groh began to celebrate the Consecration of the Human Being again in the center of Berlin, where he lived on Brüderstraße in the Nikolai-Lessing House along with Anna Samweber. He brought his will to bear with particular intensity when celebrating. On long walks through the destroyed city, he regathered the members of his congregation. But as early as 1947, the leadership of The Christian Community suspended him from his parish duties because of his rigid attitude toward social and cultic matters, so from then on he no longer celebrated the sacraments. In 1952, Groh moved to his family in Gur Husum near Jever in East Frisia.

Herman Groh’s unconditional devotion to the absolute, to the spirit in thought and will, which he had learned from Hegel, had something exclusive, even one-sided about it. He was radical in this and used to demanding everything from himself and others. It testifies to his spiritual energy that he would read the entire Gospel of Mark standing up every day during Holy Week. He had divided it into 96 sections and he recited the Lord’s Prayer after each section. He remarked laconically that it only takes about four hours if done without stopping.

In addition to serious, faithful pastoral care, training his spiritual capabilities was important to him. He studied anthroposophy just as seriously. He vigorously and repeatedly worked through Rudolf Steiner’s four basic books according to the seasons of the year. He read the Old Testament in the original Hebrew. It is certainly a missed opportunity that he was not tasked with retranslating at least certain parts of it.

Although he burned whole stacks of manuscripts with translations, some things were saved. Groh’s life’s work can be seen in his work on the rhythms of the Old and New Testaments. He explored these rhythms in his daily polyglot studies. He always studied the Greek, Latin, English, French, and German texts in parallel, and in the case of the Old Testament he added the Hebrew text. He indicated his findings on the composition and rhythm of the texts with markings in his edition of the Bible; many people today use them as a study guide.

Groh studied the quality of time in general. He was convinced that one should be able to distinguish a Wednesday from a Thursday “atmospherically” at any time, even in a dark dungeon. Another leitmotif was the study of the Holy Scriptures over the course of the year. Additionally, he researched English and American literature for the occurrence of occult events. And finally, he always read as many international newspapers as possible.

He had thus been going along tirelessly engaged in learning until, after 63 active years, 12 of which he was forced to spend as a soldier and prisoner, a short, serious illness ended his life. This man of the world, who had come to know, understand, and love this earth and its peoples so fully, the priest, who had worked on himself so assiduously and was always available for people to talk to: now he was entering the world to which, after all his studying, praying, and meditating, he felt he belonged.

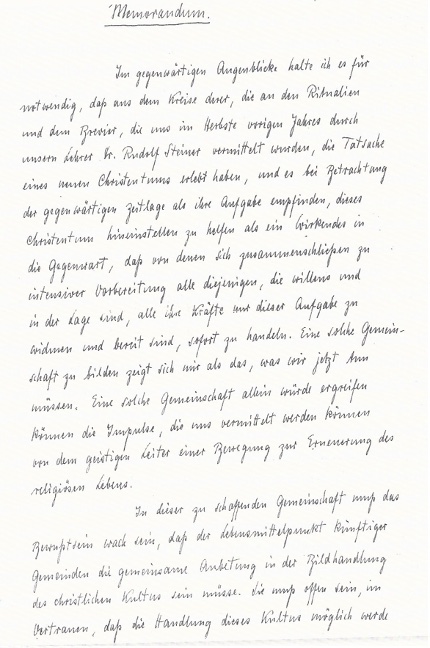

MEMORANDUM

At this moment in time, I believe that those of us who experienced the new Christianity imparted to us last autumn through the rituals and the breviary by our teacher Dr. Rudolf Steiner should, considering the present situation, feel obligated to help establish this Christianity right now as an active and influential force. Furthermore, those of us who are willing and able to devote all our energy to this task alone and are ready to act immediately, should start making intensive preparations together. Forming such a community strikes me as the necessary step now, as only this kind of community would be able to grasp the impulses imparted by the spiritual leader of a movement for the renewal of religious life.

This prospective community must hold in its consciousness that the focal point of future congregational life must be communal prayer in accordance with Christian rituals. The community must be an open one, trusting that the performance of these rituals will be made possible through a new connection to the spiritual stream that began with the deed of Christ and continues with the living Christ, a new beginning that will be given to people in due time.

This community can become strong through a life in Christ.

This community will work out of the power of Christ to reorganize of all areas of life and to create new forms of living in community with a view toward the work in future congregations.

Many questions have arisen among us since the Dornach course. Many practical details are still missing, and much of what we do have needs further elaboration. We must ask Dr. Steiner to help us continue our preparations.

I am resolved and prepared to join forces with those who see their life’s task as spreading the new Christianity. I will leave all past commitments behind and am ready to start work immediately. I request to shoulder the karma of the community, and I hope my own is not too heavy for the community to bear.

Berlin, March 4, 1922 Hermann Groh

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!